The de Young Museum in San Francisco has just opened a terrific new exhibition, Alice Neel: People Come First, the latest in a group of Bay Area shows focusing on the work of important but relatively unknown 20th-century American women artists.

First there was a retrospective of the prolific feminist Judy Chicago last fall at the de Young, featuring her often polemical works across several media. This was followed by the elegant paintings of abstract expressionist Joan Mitchell at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

The Alice Neel show presents more than 100 works from the artist’s 60-year career, with a particular focus on her closely observed, colorful portraits of friends, lovers, family, and ordinary Americans. Most of the portraits are simply staged, with minimal backgrounds. The subjects wear ordinary street clothes and gaze directly back at the viewer. There are also nudes — lots of nudes — sitting, standing, reclining, pregnant.

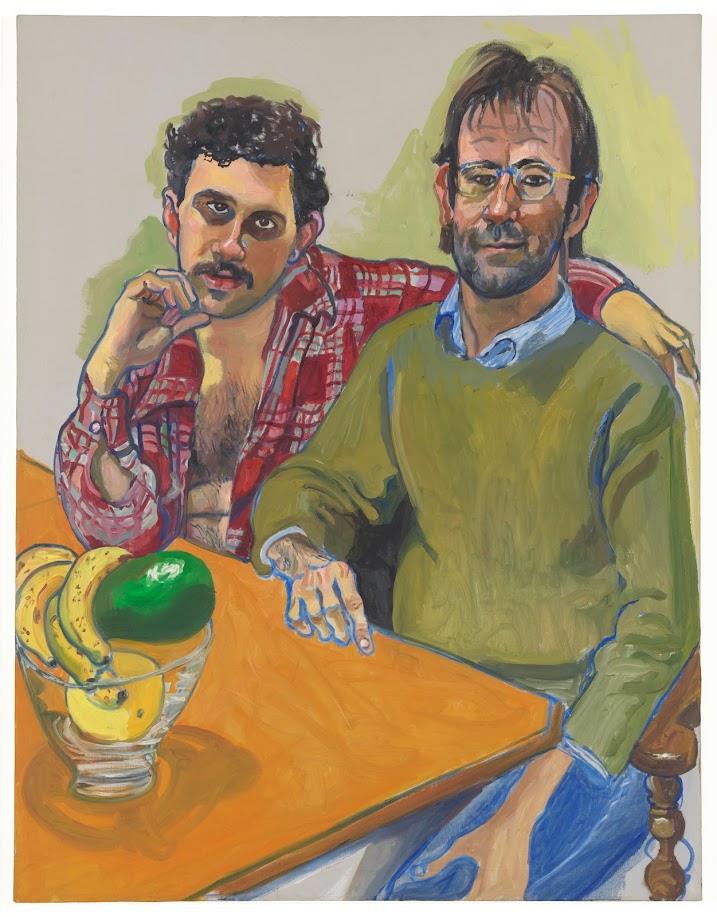

In Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian of 1978 (right and detail in top image), Neel seats the artist Hendricks and his partner Brian Buczak at her plain kitchen table and adds only a bowl of fruit as decoration. Brian, with curly black hair, penetrating dark eyes, and an unbuttoned plaid shirt, puts his arm around Geoffrey, who smiles slightly. It’s a sweet but intense image of the pair, and a fine example of Neel’s mature style.

Neel (1900-1984) traveled a long road to reach the honest assurance of Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian. Born to a middle-class family in suburban Philadelphia, she trained as an artist at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, where her teachers included Robert Henri, a member of the gritty Ashcan School of realistic painting.

Soon after graduating, she married a Cuban artist, Carlos Enriquez, and moved to Havana. There she had a daughter, who died within a year, and then a second daughter. By 1930 she was separated from her husband and daughter and had moved to New York, where she would live for the rest of her life. She had a nervous breakdown and was hospitalized for a year. After her recovery, she plunged into her bohemian life again, with affairs and eventually two sons.

As a leftist in Depression-era New York and an artist in the WPA Federal Arts Project, Neel painted portraits of her fellow political activists and contributed illustrations to leftist magazines. But she also created moody streetscapes of poor neighborhoods that still retain a creepy power.

A powerful example of those street scenes is Ninth Avenue El of 1935. The complex composition includes a forlorn pair of men loitering on the corner of 14th Street at night while a woman and child cross the avenue. Above them two dark figures with skulls for faces cross a walkway to the elevated subway line. A bus rumbles under the El while a train approached in the distance. The painting captures the bleakness of the Depression, with echoes of 1920s German expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Ashcan School artists such as Edward Hopper.

As the art world moved to abstract expressionism in the 1940s and ‘50s, and then to Pop Art in the 1960s, Neel stuck with her own style of realism with a leftist slant, often using neighbors and friends as subjects. The Spanish Family of 1943, for example, presents a poor Latina woman and her three young children, relatives of Neel’s lover at the time, when she lived in Spanish Harlem. The mother stares ahead, looking exhausted; the children look afraid, and probably hungry. It’s a powerful image of poverty.

Neel’s two sons had their own anxieties as well, to judge from Richard and Hartley, her revealing 1950 portrait of them. Richard, the older son, clasps his hands together and stares off slightly to the side. Hartley casually rests one hand on his brother’s shoulder and stares directly at the viewer (or his artist-mother) with huge, pale blue eyes. They’re alert, intelligent-looking boys, but hardly a pair of carefree suburban kids.

Near the end of her life, Neel created one of her strongest, most breathtakingly honest portraits in her entire career. In her nude Self-Portrait of 1980, she sits in a blue-and-white striped chair, holding a paintbrush in her right hand, a white cloth in her left, and wearing nothing but her eyeglasses. At age 80, her hair is white, her breasts and belly sag. Yet her defiant expression seems to say, This is the truth, get used to it.

Alice Neel: People Come First was organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and runs through July 10 at the de Young Museum, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. An extensive catalog is published by the Metropolitan Museum and Yale University Press.

Top image: Alice Neel, Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian (detail), 1978, oil on canvas; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, purchase by exchange through an anonymous gift, © Estate of Alice Neel, photograph by Katherine Du Tiel.