Apart from openings, it’s rare to visit a gallery show at the same time as the artist—and the artist’s rooster—and be offered a private tour of the work. Such was the case when I stopped into the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (ICALA) recently for Carmen Argote’s “I won’t abandon you, I see you, we are safe,” and Argote happened to be arriving just then. She brought with her a clutch of newly-laid eggs from her chickens to arrange along the baseboard under some of the pieces in the show—footnotes, if you will. Accessories. But also exclamation points. As a result, I learned my first lesson about this multi-media installation: it is evolving; it is an interaction of forms; it is a revaluation of institutional space; it is collaborative; it is a performance and an intervention. Argote’s commitment to process is, no doubt, the hallmark of her show; process serves as her approach but also as her partner. It is the ghost in her machine.

What she’s getting at through this primary creative process—and as she continues the processing of experience during her show—is a long, often recuperatory, look at identity, both as a concept and as a personal practice. Not an identity that is static or germane, but rather one that is fluid and changeable and “other” than the identity we might associate with a story of origins. The show’s title—“I won’t abandon you, I see you, we are safe”—suggests a narrative built around an inner child and thus interrogates the concept of “mother,” which is a word that appears literally in the work hung on the walls, but also is a concept we can extrapolate from such materials as the eggs. This is the riddle of origins—what comes first, the chicken or the egg? the mother who raised us as children or the mothering we must do for ourselves, for our inner children, as adults? It should perhaps be acknowledged that Argote’s beloved flock of chickens, responsible for laying these very eggs, bear the names of her artistic influences—names such as Paul McCarthy, the Los Angeles artist known for his “paintings in action” and the use of his body as a paintbrush, and Carrie Mae Weems, whose installations and video projects center the experiences of women of color. These are the show’s ancestors—not biological but rather ideological, philosophical, and aesthetic.

More than once, Argote presents mixed-media pieces that include the word “MOTHER,” repeated as block letters in a raised imprint, which then become a site of intervention. Red or black lines snake around and through the letters, dissecting the word and forming alternatives—now we see “other,” now we see “her,” now “moot” or “too” or “there.” The recombinant letters create new possibilities, not just for a new relationship with a mother, but for a new relationship as a mother—mothering the self. For Argote, origins are mutable—a puzzle to be rearranged— and artistic expression is a constant negotiation between interior and exterior forces, between physical and psychological realms, between the self and the world we walk through.

Speaking of walking, Argote’s daily walks inform her making process and the materiality of the works she creates, as do other daily rites and rituals and their attendant bodily processes. Case in point, she hunts for oak galls on her walks that then produce the ink she uses to create many of the art works. But the husks of the galls appear as well, in large textural drapes that hang heavy on the wall, more sculpture than textile. Argote lines the dried galls up in dark rows to again spell out “Mother” or “Other,” and the anagrammatic possibilities of language echo eerily in these little bowls that look like open mouths wanting to speak. Like the mixed media prints, this weaving rearranges the word “Mother” into a new thing, into new words that reflect difference (like “other”) or that might offer a challenge to identity (like “her”).

Moreover, the entire show is full of work made from the output of bodies—tree, chicken, and human. Argote plays with the idea of what can be made from the extractions, the functions, the processes, of living things: the eggs lined up against a wall; paintings made with the ink of oaks; washes made of her own urine that stain the paper a luminous color; prints that include chicken excrement. And everywhere in the paint are fingerprints, handprints, footprints, torso prints—her own body used not just as a source of materials, but as a tool. The work foregrounds the body in the similar way to Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta, who framed her body in and on the ground, as earthwork: “Through my earth / body sculptures, I become one with the earth … I become an extension of nature and nature becomes an extension of my body.”[1] In her use of bodily processes, then, Argote can provoke a discussion about what it means to have a body and what it means to challenge normative definitions of that body, as a site of individuality, as a site of gender expression, and ultimately as the site of artistic production itself. The effect of leveling the artist and her process with the art she produces is what Los Angeles art critic Amelia Jones has identified as necessary to “replot the relationship between perceiver and object, self and other.”[2] In other words, we all become part of the creative process—an aesthetic gestalt, if you will—which is in flux and open to change, to making up as we go.

Another way she mends a wounded self and makes a new story is through her many so-called “comforting objects,” positioned around the gallery floor. As the name “comforting object” implies, they resemble recumbent dolls, or perhaps small mummies since they are netted and knotted of natural materials—palm fronds and strips of clothing or lengths of rope—rather than made of plastic or porcelain. In any case, the sculptural forms again embody a sense of process because they are created from braids—each thick strand made up of three lesser strands. Argote explained that the braiding functions not just as a design element, but conceptually, as a trope for the act of integration, where she imagines disparate elements and experiences woven into one. Like the anagrams she creates from twisting the letters in the word “Mother,” here she twists palm leaflets together to create a new version of the material. I suspect she imagines the title of the show similarly—“I won’t abandon you, I see you, we are safe” is a statement forged in triplicate, stronger and more durable because of it. Thus Argote’s reconceptualization of these “comforting objects”—presumably meant to comfort this inner child that is now safe in the embrace of new contexts—transforms them into anti-effigies, not intended for the purposes of ridicule or punishment, but rather as opportunities for solace during a protracted process of self-fashioning. Argote’s sense of self aligns with what feminist critic Donna Haraway has called “the wild facts that will not hold still.” Haraway insists that when we make up a self, we are “making oddkin; that is, we require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become—with each other or not at all.”[3] Indeed, Argote’s mode of creativity exemplifies this versatile identity.

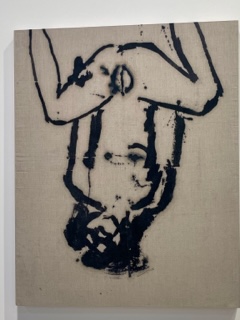

Perhaps the most imposing piece in the show is Argote’s Gynecological Fantasy, positioned exactly at the midline of the gallery’s back wall. It is a large figurative sketch, a dark outline of her crouching body, legs splayed open, somewhat reminiscent of a Tracey Emin painting without the color. The seemingly continuous line of brown ink is rendered from the oak galls, and its effect on the neutral linen canvas is to bleed ever so slightly into the cloth, so that the figure appears to soften at the edges, its porousness suggesting mutability. It is also upside down. This female body—in its most naked, vulnerable position—will insist on seeing the world from a different perspective, and, in that sense, fulfills a similar function to The Hanged Man card in tarot, complete with a sense of surrender and of gaining a new identity by flipping experience on its head. This piece’s atonal title is at once tepid and scientific and then torrid and imaginative. The figure strikes a birthing pose in its exposed squat, but its overall inversion makes it a non-normative one.

Perhaps the most imposing piece in the show is Argote’s Gynecological Fantasy, positioned exactly at the midline of the gallery’s back wall. It is a large figurative sketch, a dark outline of her crouching body, legs splayed open, somewhat reminiscent of a Tracey Emin painting without the color. The seemingly continuous line of brown ink is rendered from the oak galls, and its effect on the neutral linen canvas is to bleed ever so slightly into the cloth, so that the figure appears to soften at the edges, its porousness suggesting mutability. It is also upside down. This female body—in its most naked, vulnerable position—will insist on seeing the world from a different perspective, and, in that sense, fulfills a similar function to The Hanged Man card in tarot, complete with a sense of surrender and of gaining a new identity by flipping experience on its head. This piece’s atonal title is at once tepid and scientific and then torrid and imaginative. The figure strikes a birthing pose in its exposed squat, but its overall inversion makes it a non-normative one.

As such, Argote’s process not only refers to the primary act of making but also to an ongoing elaboration and extension of the work. Her show continues to birth new content, and, as such, it too functions as a braid—Argote keeps pulling new strands of meaning and experience into it that serve to disrupt the idea of a static or finished exhibition. The ICALA space really becomes more like a studio than a gallery for Argote, and thus she can make good on the claim of destabilizing the institutional white cube. The museum visitor won’t see the same show one week that they will see the next. It keeps changing, shifting, becoming something else. These interventions are deeply collaborative—not just with chickens and trees—but with friends, colleagues, lovers, museum guests, and family. In fact, Argote and her mother collaborated on some of the performances that have been held sporadically in conjunction with the show. These events take place in a mobile “playspace” surrounded by the art, and—at this one—she and her mother bound and unbound each other with rope, in the fashion of shibari.

Argote’s processes, whether ritualized or spontaneous, enact change. She is braiding a new self out of where she started, and it is fluid and multiple—and inclusive. As audience members, we can’t help but be implicated. It doesn’t require an impromptu tour with the artist to see that this show has made space for all of us—in fact, has insisted on our place at the table (or on the walls, as the case may be … on one wall of the gallery, Argote has hung questions from museum visitors, which she answers with words and drawings). We become part of the dense collage she activates within this space and then carry those vibrant possibilities with us as we leave.

Carmen Argote: I won’t abandon you, I see you, we are safe @ ICALA, June 10 –September 10

*

[1] qtd. in Ramos & Yabarra-Frausto, Our America: the Latino Presence in American Art, Smithsonian, 2014, p. 235.

[2] Amelia Jones, Body Art/Performing the Subject, UP of Minnesota, 1998.

[3] Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Duke UP, 2016, p. 4.