A sprawling retrospective of work by Ed Ruscha, the quintessential L.A. artist, has just opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and it’s a knockout.

The exhibition is organized chronologically, starting with a pair of galleries featuring his breakthrough Pop Art paintings of the 1960s that made him a star. Some mimic the style of billboard advertising, while others play with the typography of words. “Oof” of 1962-63, for example, couldn’t be simpler, with the word OOF in bright yellow capital letters displayed against a dark blue background. It packs a punch.

Ruscha (1937- ) grew up in Oklahoma City and moved to Los Angeles in 1956 to attend Chouinard Art Institute (now California Institute of the Arts). He repeatedly drove back and forth between the cities to visit his parents, and these trips provided one of his most famous subjects, a Standard Oil gas station on Route 66 in Amarillo, Texas.

In one version, Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half of 1964, the station’s roofline and towering sign divides the canvas in half on the diagonal, creating a monumental image from a mundane building along the highway. In an odd detail, though, a small comic book — the 10-cent Western of the title — flutters in the breeze near the top right corner. What it means is anyone’s guess.

Ruscha deploys a similar strategy in Actual Size of 1962. In the upper half of the squarish canvas, the word SPAM is painted in bright yellow against a dark background. In the bottom half of the large canvas, a can of Spam emits a yellow flame as it appears to fall toward the lower right. Is it a comet from the Spam galaxy? A Spam-fueled satellite falling to Earth? Or Ed Ruscha just joking around?

The early galleries also contain works that focus on another of Ruscha’s obsessions — the city of Los Angeles, its streets and buildings. One of his most famous subjects, the Hollywood sign, appears in several, including a luminous screenprint, Hollywood of 1968 (above and detail in top image). Unlike the actual sign, which is white and sits on the side of the Santa Monica Mountains, Ruscha’s sign has a golden glow and is placed at the top of the mountains and below an evening sky. It’s truly an iconic image.

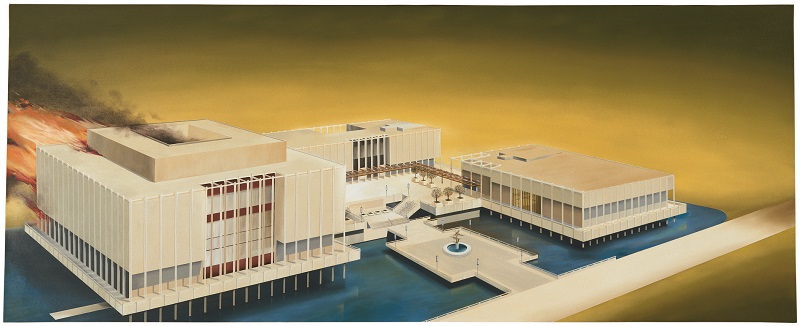

Another 1960s work featuring an L.A. landmark carries a particular irony. Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Fire of 1965-68 shows the original buildings of the museum, now destroyed to make way for a new version. Flames bellow out of the rear wall of the old Ahmanson wing on the left. The neighborhood surrounding the museum is erased entirely, making the buildings look a lot like an architectural model sitting on a table.

Ruscha didn’t just paint the city of Los Angeles; he also photographed it over and over. In 1966 he self-published Every Building on the Sunset Strip, which includes deadpan photos of exactly what the title says. He also photographed L.A. parking lots, palm trees, and more.

By the 1970s and ’80s, Ruscha had moved on to another word-based style, offering banal or sometimes nonsensical slogans on top of colorful backgrounds. Some are as simple as “ARTISTS WHO DO BOOKS” (on a black background) or, ironically, I DON’T WANT NO RETRO SPECTIVE (on red). Others are more elaborate, such as THE STUDY OF FRICTION AND WEAR ON MATING SURFACES (on a background of streaked reds, oranges, yellows, and black). The works can be verbally clever, but visually they begin to seem repetitive when you face a dozen of them in a single gallery.

In the late 1980s, Ruscha’s work became darker, literally, often painted just in black and white, and often based on photographs. In the 8-foot-wide Brother, Sister of 1987, for example, two big clipper ships in heavy seas heel over in the wind. The ships are shown as black silhouettes, and the framing of the scene tilts the boiling surface of the ocean diagonally up to the left, the same visual trick used in the Standard Station paintings.

In Ruscha’s most recent works, the cheerful wit of his early paintings has been replaced by something much more somber. In Our Flag of 2017, for example, the Stars and Stripes is shown flapping in a strong breeze against a black background, not a blue sky. And it’s literally falling apart, with bits of red and white cloth flying away from the flag to the right of the picture. Maybe it’s a commentary on our current politics; maybe it’s pointing to some broader shredding of the culture.

A similar gloominess is present in Psycho Spaghetti Western #7 of 2010-11. This huge landscape painting of a garbage dump, more than 11 feet wide, shows a hill slanting up diagonally to the right and covered with household debris. There’s a broken lamp and shade, a tipped-over bookcase, wooden shipping pallets, strips of pink and blue cloth, and a discarded painting canvas. Looking closely at the bottom of the heap, there’s a copy of the very same 10-cent Western comic book that flew past Ruscha’s Standard Station in 1964.

Ed Ruscha / Now Then runs through October 6 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5900 Wilshire Boulevard. The show was organized by LACMA and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where it was on view in late 2023 and early 2024. An extensive catalog is available.

***

Top image: Ed Ruscha, Hollywood (detail), 1968, screenprint; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Museum Acquisition Fund, © Ed Ruscha, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.