Recently, I was privileged to interview distinguished post-modern poet Alan Britt (“AB”) by email for Cultural Daily.

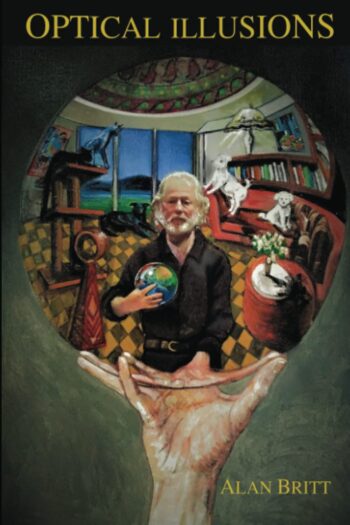

I was introduced to Britt’s writing when, knowing nothing about him personally, I favorably reviewed his previous poetry collection Gunpower for Single Ball Poems (Rain Taxi, June 2021, print edition). We’ve become acquaintances since then, and when I found out he had a new book out from Concrete Mist Press, I thought it was a good time to interview him and get an updated notion of what he’s all about.

I discovered that, above and beyond his nomination for a 2021 Humanitarian award from an international group, his 20 published poetry books, his editing experiences, and his teaching contributions—Britt’s the real deal, an internationally acclaimed poet-teacher-humanitarian. I respect that.

Here’s what happened when I interviewed poet Alan Britt.

***

Mish Murphy (MM): In about 1970, you started a literary movement that encompassed a group of poets called the “Immanentists.” I’ve researched and studied Immanentism, but can’t pass up a chance to hear your perspective. (You’re a primary source where Immanentalism is concerned, which is great.)

AB: Thank you, Mish, for the kind words and the opportunity to clarify a few things. Our teacher and guiding light for the Immanentist movement that included many poets and a few visual artists was none other than the infamous Duane Locke. At the time, Duane was the most published poet in the U.S. and highly influential (along with Robert Bly, James Wright, Charles Simic, Robert Kelly, Jerome Rothenberg, Diane Wakoski) for poets to write in what was then known as Leaping Poetry and/or the Deep Image style.

The Immanentist movement at the time was extensive and included over 30 poets and visual artists. The core members still writing and painting today include Steve Barfield, Silvia Scheibli, Paul B. Roth, José Rodeiro, Charles P, Hayes, Stephen Sleboda, Anthony Seidman, Nicomedes Suárez-Araúz, and myself. I’ve likely left out a few folks I’m no longer in touch with—sorry for that!

The Immanentist group was first called the Linguistic Reality poets (not to be confused with the later L-A-N-G-U-A-G-E poets). Linguistic Reality makes the most sense to me because the term suggests that the poetic text itself is a living reality, an experiential lexicon and not mimetic or a philosophical musing about subject matter that is separate from the text. The text creates its own reality.

I’m aware that such definitions can easily veer off into Cartesian nonsense or phenomenological ambiguity, so to simplify—we wanted our poems to engender a full body experience that was emotionally intelligent.

Anyway, one of the basic tenants of Immanentism was that through text and paint we could fuse consciousness with the natural world akin to the spirituality achieved via terrestrial veneration practiced in Native American cultures. At the time we felt that conceptual language—the language of ideas and factual information—was not conducive for such spirituality, hence, the reliance upon a more surrealistic (linguistically nuanced) approach for our poems.

MM: I loved reading your recently published collection Optical Illusions (Concrete Mist Press, 2021) because it’s humorous, sometimes unexpectedly. What kinds of humor, classical or contemporaneous, do you enjoy?

AB: Humor was one of my earliest loves. My mother was very funny, and her friends were a riot. I’m attracted to topical humor, à la George Carlin, as well as to the silly and often intelligent humor of Steve Martin and Monty Python. Samuel Clemens’ sardonic and often understated humor is particularly funny to me.

MM: Have you ever had an important epiphany or similar experience—about something related to your writing?

AB: Hmm, interesting question. There are times when I feel as though I’ve left my body while writing poems. Sometimes I’ll begin a poem and completely zone out to where I hear a voice speaking words inside my head, so I’ll write as fast as I can just to keep up with that inner voice. When I’ve finished, I’ll wonder who was that voice speaking to me? I hear the voice clearly in a manner that doesn’t feel as though I’m the one generating it. Such experiences—not unlike lucid dreaming—can go on for 45 minutes or more. I then review the text to see what I’ve written only to realize that some voices create better poems than others!

MM: As a poet who’s also a university professor, what lessons about writing have you learned in the process of teaching others to write?

AB: I teach a variety of poets in my classes, and their diversity of styles has been immensely gratifying. I discover and rediscover poets all the time. Reading poets closely for class discussion reveals the wonderful layers inherent in their work. Such patience with a poet’s text is the way to go.

I’ve learned through explication how to fully experience a poet’s language, how to engage with my senses what each poet has to offer. There’s nothing like preparing notes about a poem for discussion that takes you deep inside a poet’s linguistic nuances. Patience is required but the reward is well worth it.

I practice this deep reading often and thoroughly enjoy new books I receive even though I’m unable to teach all of those books. You know, students sometimes add insights that I hadn’t realized, so sharing the poetry with students is also a great reward.

MM: What can your readers, followers, and fans expect from you in the future?

AB: Well, I’m prolific by nature, and I love diversity in poetry, so I never know what approach I might take with a poem. Optical Illusions that you mentioned was written during a time when I was teaching classes in Dada and Surrealism, hence, the whimsical nature of some of those poems. Thank you to Heath Brougher for bringing that book to light through his Concrete Mist Press.

Another book, Emergency Room, is about to appear from David Churchill’s Pony One Dog Press. That book shares a bit of dark whimsy with Optical Illusions. I would like to point out that David Churchill published a book called Poetry & the Concept of Maya that includes his commentary on various poems of mine. David’s insights into my poetry have been enlightening. I thank David for taking such an interest in my work. Every poet should be so lucky.

All I can say is that the future is wide open. I don’t know exactly where I’m headed with poetry, and I want to keep it that way!