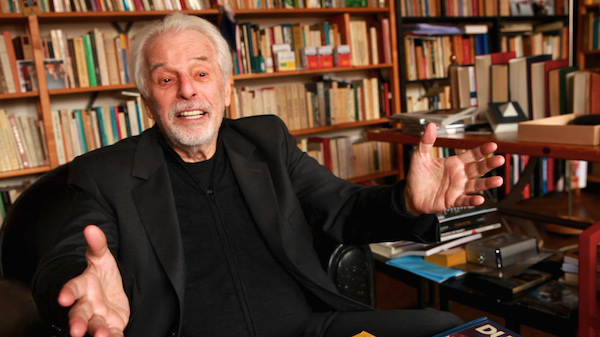

I am not sure that Jodorowsky’s film adaptation of Frank Herbert’s seminal novel, Dune, would have actually been “the greatest film ever made,” as director Jodorowsky attests had it been realized; however, I am certain that Frank Pavich’s documentary about Jodorowsky’s gargantuan and inspired efforts to make the picture is one of the most profound and entertaining films of all time about the creative process. Eighty-five year old film director Alejandro Jodorowsky is a spellbinding storyteller – crazy and egotistical by turns, charismatic and fully alive!

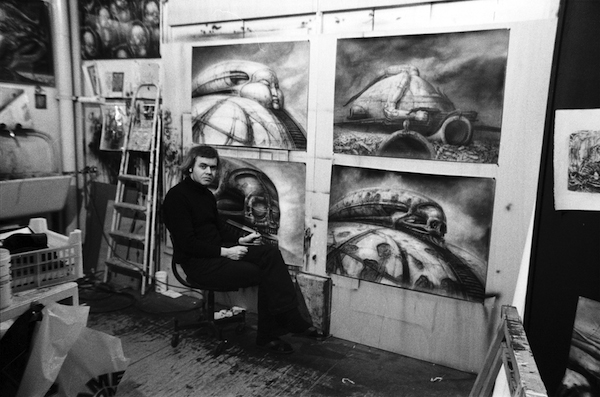

The documentary shows how this mad Pied Piper assembled a team of “spiritual warriors,” as he dubbed them — visual artists, rock stars, actors and celebrities to bring his opus to life. Among those he had drafted in service to his dream: H.R. Giger, Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud, Pink Floyd, Mick Jagger, Orson Welles, David Carradine, the list goes on. The story of Jodorowsky’s courtship and seduction of Salvador Dali, who agreed to appear in Dune, as the Madman of the Galaxy (provided that he was paid $100,000 a minute), this story alone is worth the price of admission.

The film succeeds in capturing all the exhilaration, as well as the risk for devastation and loss, central to any worthy creative endeavor. The documentary is elucidating about the nature of adaptation, and it tells a moving story of reconciliation and forgiveness between co-collaborators who have suffered together in the trenches and arisen reborn from the ashes.

My only previous association with Dune was David Lynch’s unfortunate 1984 adaptation, which many of us had awaited with such anticipation, and yet received with such disappointment. So I did not anticipate the powerful punch that Frank Pavich’s documentary, Jodorowsky’s Dune, would deal.

Jodorowsky believes that “movies have, mind, power, and ambition.”

“I wanted to do something like that, why not?” he defends. By the end of the film, Jodorowsky had seduced me, and you too may find it difficult to resist his passionate vision and poetic charms.

I recently had an opportunity to speak with director Pavich about his first feature, Jodorowky’s Dune, and his own return to directing, about the transformative power of art, and the possibility that Jodorowsky’s Dune may yet, one day come to fruition.

Sophia Stein: With his film adaptation of Dune, Jodorowsky states that his intention was to replicate for his audience the experience of LSD-induced hallucinations, without having to take the LSD. He wanted to open the minds of viewers to possibilities.

Frank Pavich: Exactly. When you see some of his earlier films — let’s take The Holy Mountain, for example — that is certainly an LSD trip without the LSD. It is a true psychedelic experience … but a spiritual one. I think every person comes away with something different when they see that film. Every time I see it, I come away with a different feeling, a different emotion, a different attitude about everything. It is what Jodorowsky strives for in all of his work. You can’t really describe in words what the film is about or what you feel. It’s fascinating. You must go see it.

S2: Encouraged by his producer Michel Seydoux, Jodorowsky led a whole team of artists that included HR Giger, Jan ‘Moebius’ Giraud, and Chris Foss to create storyboards for every frame of the film and artwork detailing intricate set and costume designs. They bound these into a book that they copied for all the Hollywood studio heads. Did you ever get a chance to read Jodorowsky’s storyboard book for Dune, cover to cover?

FP: I have read that book all the way through. And I have read his screenplay as well. Jodorowsky went to The Casbah for two months to write the screenplay. It is interesting because not only do the storyboard book and screenplay differ in many ways from the source material, Frank Herbert’s novel, they also differ from one another. It is a reflection of how Jodorowsky’s vision and ideas are constantly evolving and mutating.

S2: Jodorowsky compares a director adapting a novel for a film to a groom consummating his marriage vows. “The bride is in white, and if you respect the bride, you never have a child,” he observes. “I was raping Frank Herbert … but with love.”

FP: Exactly. “Jodorowsky was looking at the Dune novel as literature, not as a manual,” my composer noted the other day. Jodorowsky was just getting inspiration from the novel. He claims that he was divinely inspired to chose to adapt Dune in the first place. He chose the novel without [ever having even] read it! In fact, I believe that all of his choices throughout the entire creative process were divinely inspired. Jodorowsky looks to the heavens for inspiration more than anywhere else.

S2: How were you divinely inspired to take up telling this story of what might possibly be “the greatest film never made”?

FP: The tale of Jodorowky’s Dune had been floating around in the ether of public awareness for many years, but only little bits of it existed here and there. There had never been a definitive telling of this story, and we wanted to be that definitive telling. We wanted to learn more. The images were out there, but they weren’t available. That’s where it first started.

S2: You have described Jodorowsky as a Pegasus? How so?

FP: When I went to first went to meet Jodorowsky in his Paris apartment, I wondered, what kind of a creature would I meet? Was he a real man? Did he breath oxygen? Have red blood? I was terrified. I couldn’t believe that Jodorowsky lived in a real place — as opposed to the woods or a tree or something. Jodorowsky lives in a regular place, and sleeps in a bed, as far as I understand. Maybe it’s a bed of nails – but I think it is probably a real mattress. It was a overwhelming to be in Jodorowsky’s Paris apartment with all of his books and works are everywhere.

Photo by David Cavallo, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

S2: When you start a documentary, you have an idea about the story that you are going to tell and expectations about what you may discover, and then it evolves. What discoveries did you make along the way that surprised you?

FP: What surprised me is what the documentary turned into. It was a cool story, but I didn’t really know how amazing and magical Jodorowsky’s personality is. I didn’t really know about his attitude towards Dune. He didn’t view it as a failure; he views it as an amazing triumph. I did not know about all of the films that seemed to have been influenced by Jodorowsky’s work on Dune. I knew about Alien; it is obvious that Alien would not have happened without these people coming together in the 1970’s under Jodorowsky’s leadership. But until we were going through the storyboard book, we didn’t realize all the other films that we would recognize. We would turn a page and think, where do we know this from? Oh, Star Wars. Or Blade Runner. Or The Matrix. There were constant revelations.

S2: After being rejected by the Hollywood studios, did Jodorowsky actively give up on filmmaking or on Hollywood, or both? Or did he consistently try and try again?

FP: He did not try again to work within the Hollywood system. He knows that is not the place for him. In Hollywood, he can’t have the freedom that he needs to tell his stories. He definitely did not give up on filmmaking. It is just very difficult for Jodorowsky to get funding for projects. Since Dune, he had really made three movies — Santa sangre (1989); Tusk (1980); and The Rainbow Thief (1990). Santa sangre is a Jodorowsky classic. But Tusk and the Rainbow Thief are two movies that he disavowed. He doesn’t like the way they turned out; he felt that he lost control of them. And really, that was all he made, until his latest film, The Dance of Reality (La danza de la realidad, 2013). It had been twenty-three years since his previous film. Jodorowsky has had many ideas and many projects that almost came to fruition, and then fell apart for various reasons, usually funding. So it’s been a challenge — even for someone as amazing as Jodorowsky, it is still difficult to actually realize a film.

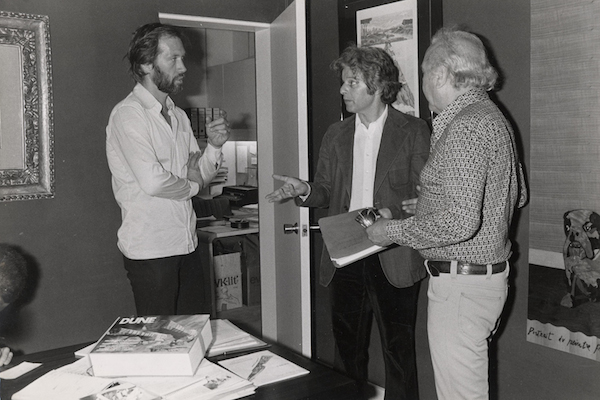

S2: Your documentary fostered the latest collaboration between Jodorowsky as a director and Seydoux as a producer. How did they come together?

FP: In fact, when I met Jodorowsky and Seydoux each separately for the fist time, they both told me that the other person hated them. Jodorowsky thought that Michel Seydoux hated him because “while we were making Dune, I cost Michel Seydoux two million dollars in pre-production. All that money is gone, and there is no film. He must think that I am not a good enough director, not a good enough artist. I let him down. Michel Seydoux must hate me!” Seydoux felt exactly the opposite. Seydoux mistakenly assumed that “Jodorowsky must hate me, because as his producer, I failed him. I didn’t work hard enough for him.” But neither one of them actually felt that way about the other. They both just missed each other.

So once we realized these two people needed to be together, we just suggested that they meet. We got them together, and they were like two old friends where not a day had passed. A few weeks later they had dinner and Seydoux asked Jodorowsky what he wanted to do next. “I want to make this film called The Dance of Reality — it’s about my childhood and growing up,” Jodorowsky confided. And Seydoux said, “Perfect. Count me in. I will give you a million dollars. Make your movie.”

S2: Were you present for that initial reunion?

FP: Oh, yes, we filmed it. There is a tiny little clip of it that we use at the end of the documentary. We just couldn’t make any of the footage work in our narrative, but it’s all there. They walked around this park in Paris; we left them alone, and let them talk to each other.

S2: I love that Jodorowsky greenlit your project with such generosity. Basically you approached him, he invited you to meet with him in Paris, and after a 10-minute interview, he said yes. “But you have to talk with Michel Seydoux because he has the artwork and the rights, and if Seydoux says no, then there is no artwork, no movie,” he cautioned. Can you describe your first meeting with Seydoux? Did Seydoux sign on right away, or did he require seducing?

FP: I basically walked into Seydoux’ office thinking, as Jodorowsky had claimed, that Seydoux hated Jodorowsky, and it was going to be a real challenge to get him involved. But when I walked into the office, hanging all over the place are original pieces of Dune artwork. Michel Seydoux has made a lot, a lot of movies! But Dune was the one that was most represented on the walls of his office, for sure. So, Seydoux lives with Jodorowsky and Dune every day. It is obviously an important — if not the most important — project of his life. So as soon as I saw that, I knew that this was a person who loved Alejandro. When I sat down with Seydoux and spoke to him about my idea to make this film, he was all over it. We spent a good hour talking. He was just regaling me with amazing tales. He was like a little kid, so inspired to start speaking about this again. Right away he said, “Yes, whatever you want! The artwork is yours; you have full access to everything. Tell a great story!” He was immediately, absolutely thrilled.

S2: Seydoux owns all that original artwork. I imagine that everybody would like to own a copy of that storyboard book with all that phenomenal artwork. Do you think that will ever happen?

FP: As far as I know, they are in negotiations. Jodorowsky wants it. Seydoux wants it. I don’t know what’s the hold-up. Maybe it’s a rights issue with the Frank Herbert estate? Because they have to go back to re-option the novel. I am sure that it is more complicated than I can imagine. Hopefully, one day. It would be great to see it come out. I would love to have a copy of my very own. Oh, can you imagine!

S2: Now those “look books” are the rage in Hollywood. Everybody puts together those kind of books. But Jodorowsky and Seydoux were perhaps among the very first to compile such a presentation?

FP: Jodorowsky is a trail-blazer in so many ways, as you know. Maybe also, that book is part of the reason why the film was never green lit or realized. Richard Stanley said something in an interview that didn’t make it into the film. He noted, “Sometimes there is something called TMI — too much information.” If you give the studios and all these people too much information, he posited, then you are just giving them more things to say “NO” to. If you go in there with a high-concept idea and just describe what you want to do, they get on board. But if you show them everything, that gives more people a place to step in and meddle. “Oh, that should be red, not green. That shouldn’t happen; this should happen instead.” Then before you know it, everything collapses.

S2: Like Jodorowsky, you had great early success as a filmmaker, and then took a long hiatus from directing. Were you stuck in development hell? Or unable to secure funding?

FP: It is so difficult to make a film. It is crazy. I made a documentary a good fifteen years ago. In the time since, I produced a small feature, I was in development hell, and I even sold my soul for a little while in reality TV. I worked in production management on Paranormal State, Room Raiders (for MTV), and all sorts of horrible, hideous, soul-crushing TV shows. But I let go of all of that by making this documentary, for sure. I would like to be away from that hideous world, forever.

S2: At the moment, are you exclusively focused on directing documentary films or are you also interested in working on the narrative side of things?

FP: I am not really locked-in to either. I have not exactly decided what I want to do next. Maybe I am waiting, like Jodorowsky, for some sort of divine sign from the heavens. I am waiting to find that great story that I can tell — whether it is a narrative film or a documentary. I just hope that whatever I choose to do is something that would make him proud. I share the same values that Jodorowsky strives for in his work. Like you said, he gave me this amazing, incredible gift, to be able to tell this story. He loves Dune and he loved the documentary. I would love for him to love the next film, and the next film. I would like to approach him and ask, “Hey, what do you think of this?” Whenever [Nicolas Winding] Refn makes a movie, he goes to Jodorowsky for a Tarot card reading: “Should he make this film? Or should he do that one?” So maybe I’ll try it out; see what the cards have to say. I don’t want to let him down.

Photo by David Cavallo, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

S2: Refn made a film, Only God Forgives, that he dedicated to Jodorowsky. It screened at Cannes at the same time that your documentary screened, and where Jodorowsky’s newest film also screened. Did you have an opportunity to see Refn’s film? Did you remark Jodorowsky’s influence in Only God Forgives?

FP: I went to the premiere of Only God Forgives. It was fantastic. I see the Jodorowsky influence in pretty much all of Refn’s films going back to Valhalla Rising, for sure. But Only God Forgives is pure Jodorowsky. Refn loves Jodorowsky and really looks up to him. Refn makes these films which are one thing on the surface, but are really about something so much more. I think people who saw Only God Forgives might have dismissed it, not really understanding what it might truly be about. There are a lot of layers to it. If you know that Refn is a disciple of Jodorowsky, you know that he would not make something which is just surface; it would be something a lot deeper.

So there were three films at Cannes this year which all somehow had something to do with Jodorowsky. There was actually a fourth, as well — Alejandro’s granddaughter appears in Blue is the Warmest Color along with Michel Seydoux’ grand-niece. That Cannes featured four films representing Jodorowsky and three films representing Seydoux is wild!

S2: Do you think someone will be inspired by your documentary to realize Jodorowsky’s Dune?

FP: I wonder. As Jodorowsky definitely states in the film, “It is a film that can be made in animation now, or realized even after I’m dead.” I am sure that there are people that will walk away feeling inspired to bring that story completely and fully to life. Time will tell. As the film spreads out, and more and more people see it, let’s see who starts reaching out with the burning desire to tell that story. I am sure that there will be several people fighting for the opportunity.

S2: Is it true that you are based in Switzerland now?

FP: I live in Geneva. My wife works for the United Nations. Geneva is only three hours by train from Paris, so I could go visit Jodorowsky or Seydoux at the drop of a hat — talk with them, show them things, or get my Tarot cards read … whatever.

S2: What have you learned in a Tarot card reading by Jodorowsky?

FP: I have only had one Tarot card reading with him so far. It is kind of new to me so it was a little over “my dense head.” I think I’m going to have to have more readings to fully understand it.

S2: Your documentary, Jodorowsky’s Dune, has won a bunch of awards —

FP: It won both the Audience Award and Best Documentary at Fantastic Fest, as well as, awards at festivals in France, Spain, and Finland. Fantastic Fest is a film festival that takes place in Austin, Texas. It is a “genre-ie” film festival, with science fiction and horror films and out-of-the-box type of stuff. They said that a documentary had never before won their audience award. People down there really seemed to be taken with it. It is right up their alley. So that was great.

S2: Do you believe Jodorowsky’s Dune would have been “the greatest movie ever made”?

FP: No one can say for sure … There is an argument for it in the documentary, but who knows. I wonder …

S2: About your documentary film, you say, “This is a film about a unique ambition: the ambition to change the world through art.” Is that part of your mission as a filmmaker?

FP: I think so. That’s what Jodorowsky likes to do. He says that the worst thing in the world is for someone to walk into a movie and to come out two hours later untransformed — to come out as the same person that they were when they went in. He believes in total transformation. Why would you make a film if it is just to waste somebody’s time? You are trying to teach people things, to show people things, to give them an experience that they will never forget! I am completely and absolutely of that school. It is so hard to make a movie. Why would you do it without a higher goal?

Top Image: Artwork by H.R. Giger, “Jodorowsky’s Dune.” Courtesy of H.R. Giger/Sony Pictures Classics.

For more information, see the official website for “Jodorowsky’s Dune.”