Part of the resistance some readers have to comics is that the medium’s history in America has left it dotted with unseemly and unflattering stereotypes. People envision the fans as overweight, pasty, acned, socially-awkward and/or smarmy in the vein of the Simpsons’ aptly-named Comic Book Guy. The creators, when they’re imagined at all, are slovenly, shambling middle-aged hacks steeped in pop culture escapism, hunched over their drawing boards, living life through the heroes and villains of nonsensical cosmic battles.

Anyone buying these caricatures never met Joe Sacco, but you should. I know of no single artist who represents such the antithesis of the popular conception of the comics artist, both in his life and his work. The books he creates are a revelation on many levels.

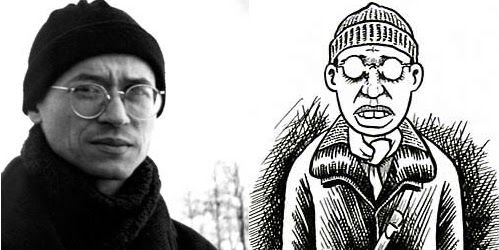

One of the ironies of Joe Sacco’s comics is that he routinely portrays himself as a gawky nerd (an odd choice, since he looks quite ordinary) while doing things few of us have the cojones to do – namely, travelling to the most destitute, battle-scarred spots on the planet to interview the populace about their experiences. I don’t credit firemen or skydivers with the nerves of steel it takes to be a war correspondent.

Neither is Joe Sacco typical among reporters. As one of the most accomplished cartoonists alive, he has positioned himself as the most notable craftsman ever in the narrow, narrow genre of comics journalism. There isn’t a close second. In eight books over a dozen plus years, he’s drawn more than 700 pages on the Israel/Palestine conflict alone and more than doubled that count chronicling violence, corruption and desperation in Iraq, India, Bosnia, Africa and, more recently, the most dirt-poor towns in the United States (not even counting his just-released silent panorama project on The Battle of Somme – the bloodiest day of the Twentieth Century). Given the sheer level of detail he crams into each and every one of his images, the man must be a drawing machine. Just look at a single, astonishing panel from Footnotes at Gaza.

Not a quarter-inch is wasted. The converging lines draw your eye to the single point of the vehicle pulling away from the reader, yet the more you take in the scene from top to bottom, left to right, the more rich detail reveals itself. The crowd scene below from Safe Area Gorazde fixes individual expressions, clothes and body language for each and every person depicted. Note the breaking window on the top floor of the background building, two different types of fences and the cars parked on the street. Few cartoonists would take the trouble, or simply have the raw talent to include this level of specificity, particularly to depict a scene he, himself never witnessed.

None of Sacco’s work is for the faint of heart, giving voice to the dispossessed and discarded citizens of our world, who spend every ounce of their energy and resources on the simple and mighty task of survival. I felt a sympathetic ache in the pit of my stomach learning about the lower caste Indians Sacco visits in his short-piece anthology Journalism, who, after days of starvation, feed themselves by stealing bits of grain out of rat holes. In the context of the bureaucrats (who refuse to be interviewed) skimming off government services that should feed these untouchables, stories like these sharpen the larger picture of the pecking order of users and swindlers. Sacco’s work is horrifying, humane, outraged and sadly informative (he’ll never run out of material). They leave the reader feeling deeply grateful for the accident of birth that allows them to afford depressing graphic novels.

While critics are united in praise of Sacco’s work, not many to date have truly taken in the full measure of his career achievement. Once he’d cut his teeth in the early nineties (and his art back then included some very large teeth indeed) with his first major work, simply titled Palestine, Sacco perfected his cartooning approach in the magnificent, heartbreaking Safe Area Gorazde. His words are all of a piece – factual narration with details, anecdotes and profiles structured from Sacco’s interviews. The visuals are the depiction of incidents as told to him and intensively researched for accuracy, or just the interviews themselves with Sacco present. The simplicity can disguise the mastery involved, since his latest book is “another one by Sacco”. Consistent excellence on dire subjects does not a pop culture splash make and writing about his books is akin to reviewing the daily paper. Sacco merely chugs along, prolifically performing his invaluable service to the planet.

By focusing in his work on the most devastated of populations, Sacco hones in on the pure essence of what it means to be human – to simply need and struggle and scrape by with whatever resources you can manage to bring your way, while protecting and caring for those you love. That is never explicitly stated in his reportage, but it is plain in the faces and stories of everyone he encounters. By drawing those interviews and the stories they reveal, he gives us the experience, so powerful and distinctive to comics, of living in these faraway places and tragedies of history – the textures of the stucco walls, the extended shadows of pawing through the forest at night and the wrinkles etched on the foreheads of the unfortunate. What’s more, the bullet-riddled buildings and muddy streets aren’t just mentioned in an early paragraph and left behind to fading memory; they’re there before your eyes in every single panel, allowing you a first-hand view of a life you’ve never lived. Joe Sacco is a one man empathy generator.

Journalism is serious business. Those who consume it for more than kittens and bikini contests are cheated if all they receive is a steady diet of press conferences plying the rationalizations of those at the top of the food chain. Sacco gives us a window into the world as unique as his singular talents, one that far transcends the diminished capacity of words like “comics” and “journalism”. What some might view as a novelty is in fact a far richer tapestry that embraces the humanity of people both far away and as close as ourselves.

In his mission to bring home the sins of the world, Sacco opens up more minds than he knows. In almost every way, Sacco confronts preconceived notions of what comics is, demonstrating the extent to which comics is an invaluable tool among the ways we comprehend and interpret the world. Sacco’s work shows that comics is as necessary a part of our media landscape as magazines, video documentaries and live streaming websites. The least we can provide such a radical artist is our attention.

Top two images with permission of Macmillan. Bottom image with permission of Fantagraphics. Photo of Joe Sacco by Michael Tierney.