From 1981 – 1984, as a young and emerging choreographer/director, Sarah Elgart taught dance and created choreography with a small group of maximum-security inmates at California Institution for Women, the state prison. Initially unbeknownst to Elgart, two of the inmates in her class included Patricia Krenwinkel and Susan Atkins of the Manson Family. When each independently elected to participate in the ten-month creation of a movement theater work, the two women had not spoke for ten years. Poetry + Murder recalls the class’s confrontations, obstacles, and epiphanies in creating “Marrying the Hangman”, an award winning work based on the poem by Margaret Atwood, before it went on to be performed via Elgart’s company in the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival. To catch up with the story, read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3.

Photos by Jaeger Smith

On November 13, 2010, after 26 years, I was on my way back to CIW. Upon filling out the necessary paperwork I had been cleared to go at any time, yet I had postponed the visit for weeks. This was in part because I was too busy, but also because I was incredibly anxious about it. Part of me felt like I would be stepping back in time, once again becoming my former twenty something year old self, walking into the prison to teach… It was totally irrational but still mildly terrifying. Beyond that, I was relying on Krenny’s recollections about the creation of “Hangman” to help me gauge the reality of my own memories and impressions, and I wondered how much of my written recollections had been romanticized over the years. Memory is so elusive and subjective… Maybe I had been living in a dream about the whole thing. And because Krenny had been such a powerful character, I felt a kind of dread at the impact she might have. I was not so much afraid of Krenny as of the information – the forgotten secrets she might have – and of what I might or might not discover about myself, and the events of that time.

I set out on a beautiful day. The mountains were visible against an incredibly blue sky with a smattering of white clouds and no trace of smog anywhere. Already so much had changed. Navigating via my iPhone, I discovered that CA-71 had been built, abridging the need to travel through the miles of open cow fields that spanned South from the I-60. The drive took an hour and 20 minutes. And although I was directionally confused, in the end the smell of cow dung, as pungent as I remembered, confirmed my arrival.

I stepped inside an air-conditioned waiting room marked “Visitors,” part of a new building annexed to the prison, and signed in. The fifty or so people waiting on this crisp November Saturday were mostly Latino, with a handful of African-Americans and Whites and one Asian woman. They were all sizes and ages – from infants to a thirty-something year-old former gangbanger with a tattooed head, to young boys with silver teeth, and elderly grandparents in wheelchairs. Realizing I had forgotten a photo that I wanted to show Krenny and worried that my name would be called in my absence, I dashed quickly out and began running to my car. A man walking in the parking lot pointed to the watchtowers with gunmen on the perimeter of the lot. “You don’t want to be running out here. They could think you are an escaped inmate and shoot.”

After just over an hour, I was cleared to walk through a metal detector and three security gates, each closing completely before the next one opened. These doors led finally to yet another clearance point adjoining the visiting area I now entered. It was a crowded room full of vending machines, similar to the waiting room of a hospital but more up beat – almost forcibly so – and the volume level was extraordinary. I saw inmates seated with friends and loved ones, everyone chatting, seeking a few moments to forget where they were and find some semblance of normalcy. Scanning the room I realized all the inmates were wearing identical clothes – crisp blue and white striped shirts and blue pants. Gone were the days of individualized jeans, sweat pants, and tee shirts that I had known. I was told to find a seat and wait, but given that Krenny had no idea what specific day I would visit, and that it had been so long since we had seen each other, I stood, hoping she would recognize me.

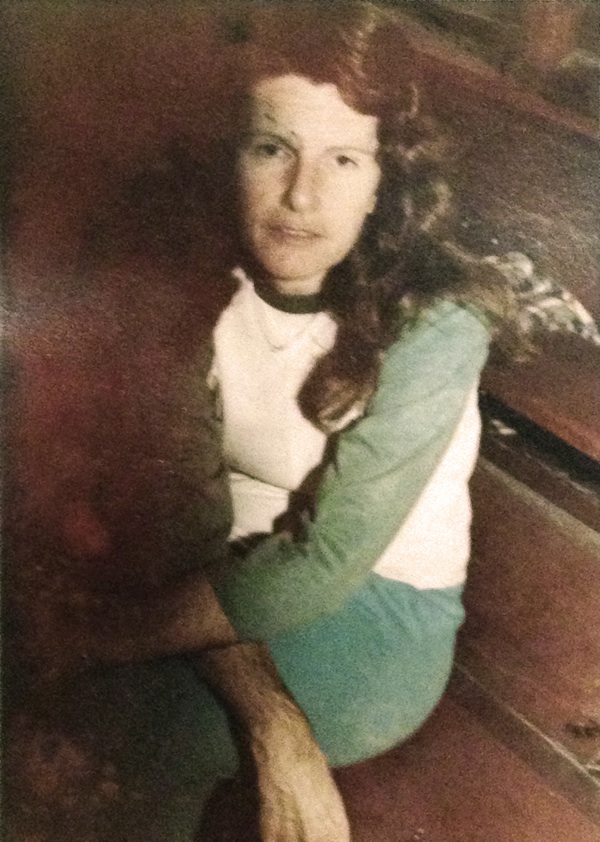

Finally, a half an hour later, I was surprised by a voice behind me saying “Sarah!” and I turned to see Krenny. We stood for an awkward millisecond then embraced. I had never hugged her before, but I felt no hesitation. Perhaps against all reason, I felt nothing but fondness and compassion. Any doubts I’d had about the importance of our work together so long ago were instantly erased. Her hug told me everything. “You look beautiful,” she said. The years had not been as kind to Krenny, who I now called Pat as per her letters. With her hair cut short and gray, she looked very different from the longhaired, somber young woman I had known. She had a wizened smile, eyes that seemed at once clear, humble and unafraid, and a spirit that was generous and optimistic. Unlike many inmates, she did not act remotely like a victim. Yet her face had the resignation of someone who kept hope alive but knew with near certainty that she would never be leaving this place.

We went outside to the patio area and found seats. I told her I half expected to see her with a dog. For the past several years, Krenny had learned to train dogs as part of a prison program to aid people with disabilities such as M.S., autism, amputations, and more. “I’m on my twelfth dog,” she said proudly. Krenny spoke animatedly and a lot, with little down time between sentences. She dived into extended explanations about using positive reinforcement while dog training. “The strongest reproach you use is ‘Unh, unh!’ when they misbehave. ‘No!’ is reserved for when they are performing a task incorrectly and it isn’t as serious.” We must have spoken for a half an hour about dog training when it finally dawned on me that she too was nervous about seeing me. Perhaps nervous about what I might ask or say, but equally likely about bridging the immense span of time that had passed since we last met.

Finally there was an opening and I changed the conversation. I asked her what she remembered about the creation of “Marrying the Hangman.” In her letters, she had already indicated her memory was often faulty, so I went over some of the factual details of how the class began, how that first day I stood on the chair and read the poem in the gym, and how the group of women that gathered around me comprised many that showed up to our first class. She nodded, listening intensely. It seemed as if a kind of sadness came over her, maybe the memory of herself at that time. When she spoke again it was more slowly, in contrast to the steady stream of chatty conversation preceding this. “I never really imagined myself dancing, before your class. In the beginning, it was terrifying, to just go through the process of moving like that. It was hard. And then later to put myself out there, in front of an audience…” She trailed off, searching her memory. “I remember that you took the dance and had it performed on the outside. That really meant a lot to us.” I reminded Krenny that the central, structural idea of having a “living wall of inmates” separating the man and the woman was hers, and that this contribution to the piece was immensely significant. She looked down and shrugged, as if hesitant to accept this much acknowledgement.

With twenty-six years and much more between us, our talk was deep and wide. Krenny shared her love of watching So You Think You Can Dance (“It’s amazing what these young people can do with their bodies. I watch it religiously!”), she talked about how different things were at CIW now from when I was there, its lack of regard for inmates and an absolute abandonment of any rehabilitative initiatives like the arts programming that had brought me there in the first place. She told me about the gradual removal of freedoms including smoking, now a punishable offense, and the mandating of uniforms for inmates. I told her how I had authenticated the story and characters in Margaret Atwood’s poem, how I had learned that the hangman was at once well paid and completely ostracized within his community along with his wife, children, and animals. We discussed dog disciplining as it related to child rearing and even to punishment… Our talk veered into areas we had never before ventured together, including how neither of us believed in God in the traditional sense, and how we thought that whatever God was, children were closest to it. And sometimes, during the course of our conversation, I felt as if I might be speaking with a peer.

At one point during this stream of conversation, Krenny spoke very eloquently, offering informed and grounded observations about the American attitude towards punishment, and how in Europe there’s a much greater focus on rehabilitation. Then, seemingly out of the blue, she relayed an anecdote that I couldn’t quite understand the origin of: “One of the murderers from ‘In Cold Blood’ chose to be shot by firing squad. Because there were so many shooters – all trained marksmen – that no one knew who fired the killing shot.” This way, she explained, no one person need have sole ownership of the execution and the ensuing guilt. Pondering this later, I wondered if this comment was a tacit and subconscious desire to share her own culpability, and compare the Manson Family, and her part in it, to a firing squad.

In the poem “Marrying the Hangman,” there is a line: “It was his only chance to be a hero, to one person at least, for if he became the hangman the others would despise him.” In speaking to Krenny, I wondered if this had been a metaphor hidden in the fabric of the poem itself that she and Susan both understood instinctively. The Hangman in the poem was a social outcast, but for the Woman he married he was a savior. He was synonymous with death in his community, so although a necessary evil in the maintenance of justice and the law, he was roundly reviled. While the Manson Family’s own particular form of evil was anything but necessary, Krenny herself, and many of the members of the Family, perhaps especially the women, joined Manson in search of acceptance and belonging. He told them they were beautiful. He made them feel wanted. For a time, he was their hangman, their savior, their lover, and their liberator. Then shortly after the murders, after the indictments, and certainly after years in prison had dampened their spirits, Krenny and Susan themselves had also become pariahs to the world outside.

I was excited to share an amazing personal coincidence with Krenny, which I only learned years after I left CIW: She and I had seen the same therapist. When I was nine-years-old, my mother attempted suicide the first of many times to come. Soon, everyone in my family was seeing a therapist, and although I was told I was strong enough to do without, I didn’t want to. I demanded to see someone as well and was taken to a woman named Bernice Augenbraun, whose strong presence and gentle patience I will never forget. Years after leaving CIW, I learned that Bernice and her partner had frequently and regularly visited Krenny and a few other inmates at CIW. With no funding provided for women to receive therapy while in prison, their services were voluntary, and greatly needed. Although it had been some years since Bernice had died, I had never spoken with Krenny directly about knowing her. It was such a remarkable connection that I seized the opportunity. “Oh I loved Bernice… She was wonderful. I just loved her,” Krenny said, smiling and remembering her fondly. It struck me as amazing that Bernice, who had been there at the most terrifying time of my childhood, later linked me to Krenny and to CIW. In fact, CIW was the place where my twenty-five plus years work with battered, homeless, and other marginalized women had begun. Only later did I realize that this work was a way to compensate for not being able to save my own mother.

Amidst our rambling talk we returned at intervals, to our time creating “Hangman” together. I wanted to know where the others were, especially Janice. As it happened, I learned, Janice had been out for years. She had come back once to visit Krenny, and they stayed in touch via letters. “You should call her. Just call her and surprise her one day, she’ll be really happy to hear from you.” I was excited about this possibility, and she promised to mail me her number.

Some of my biggest looming questions, and some of the most difficult to ask were about Susan Atkins. We had never spoken about her, and now Susan was gone. When last I had seen Krenny, she and Susan had been contentious. Was it true, I asked, that at the time she and Susan had not spoken for years until they found one another in my class? “Yes. That was true. We hadn’t spoken. And then there we each were in your class face to face.” She paused, reflecting. “Later it all gradually changed, and we each changed… Over the years we realized we had to come together again in a different way, to support each other.” I wondered if she was sad about Susan’s death. “I was sorry it all had to end that way for her,” Krenny said, and she did look sad. “Susan was teaching a Pilates class one day, and she didn’t feel well… All of the sudden she just couldn’t go on. The next day she had tubes and needles everywhere and it was all down hill from there. It just happened so quickly and suddenly. They wouldn’t even let her husband take her home to die.” Towards the end, Susan’s husband James Whitehouse had appealed for her compassionate release. The system’s denial of their request must have hit Krenny hard and reinforced the improbability of her own release, even under the best of circumstances.

After a while, a CO came out and told everyone outside to move inside. Visiting hours were coming to a close. Inside there were no seats, so we stood, still talking a few more minutes. Several inmates passed and respectfully said hello to Krenny. It was clear her seniority there commanded esteem. She answered each of them back “Hello” politely, without engaging. But then she greeted one inmate warmly, and turned to introduce me: “This is Sarah. She was my dance teacher here years ago.” Turning to me she said of the inmate: “She and I used to be cellmates and in the dog training program together. She’s my best buddy inside. We’re just two old lady friends getting older together.”

Finally, we had to say goodbye. I told Krenny I wanted to come and visit her again, and I meant it. “It was just so great to see you, Sarah,” and we hugged again. At one point in our conversation that day, Krenny had said: “Hangman was a work of art,n” with a sense of authority and ownership. Beyond any single statement, Krenny’s regard for me, for the work we had created together, her graciousness in receiving me and answering my questions was a testimonial to what we had done together as a class.

As I left Krenny, the earlier feeling of speaking with a peer was shattered. I could walk away, through all those timed doors, but she could not. And in terms of punishment, that may have been as it should be… After all these years, I still wasn’t sure.

I drove home, at once sad and exhilarated.

A week or so later I received a letter from Krenny, saying how good it was to see me, and sending Janice and Suzie’s numbers. The letter closed with, “Now you have some more catching up to do. Suzie is waiting to hear from you.”