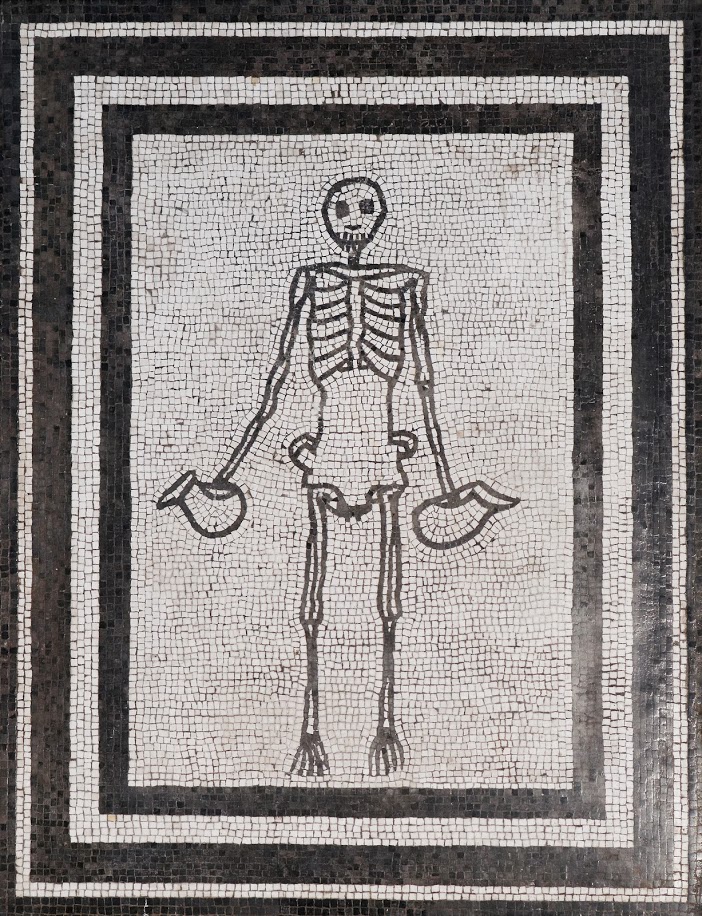

It’s an astonishing image, both creepy and endearing: A grinning skeleton, standing erect and holding two pitchers of wine, stares directly at the viewer as if to say, “It’s party time!”

The mosaic portrait, made of thousands of tiny black and white stones in the first century A.D., is one of the stars of “Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave,” a fascinating exhibition now on view at the Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco. The show features about 150 fresco paintings, sculptures, mosaics, pottery, and housewares such as silver cups and plates, all creating a portrait of how food and drink were at the center of Roman life in the doomed city of Pompeii.

Before Mount Vesuvius suddenly erupted in 79 A.D., burying Pompeii in molten rock and ash, it was a prosperous city of about 20,000 residents a few miles down the coast from present-day Naples. The surrounding area, with its Mediterranean climate, was fertile and highly productive.

Above the city, the slopes of Vesuvius were planted in vineyards, fruit orchards, and grain. Local farmers also raised pigs, sheep, and goats, providing meat, milk, and cheese. A fishing fleet brought in a steady supply of seafood. Pompeii itself sported an amphitheater, public buildings, baths fed by running water, shops, and bars. It was home to a number of wealthy Romans who lived in lavishly decorated villas, where many of the artifacts in the exhibition were recovered.

One fresco, Wall Painting With Bacchus Standing Beside Mount Vesuvius, from about 60-79 A.D., shows the local landscape with the wine god clothed in enormous grapes and accompanied by his pet leopard. Behind him is a cartoonish view of Vesuvius, and a close look shows that the slopes of the volcano are indeed covered with the same sort of grapevine trellises you might see in California wine country. In the foreground is a writhing snake, and at the top a bird rests on a garland of olive branches, complete with clusters of brown olives. It’s a portrait of the region’s agricultural wealth.

Another highlight of the show, Polychrome Mosaic Panel With a Marine Scene, from the first century B.C., shows the riches of the Mediterranean. It’s a riot of sea creatures set against a black background, with an octopus in the center fighting for his life with a large lobster. The pair is surrounded by fish of all shapes and sizes, plus shellfish, an eel, and a curious bird on the shore included for good measure. The mosaic is more than three feet square, crafted with amazing detail.

Wall Painting of a Dinner Party, a fresco from about 40-79 A.D., shows where much of that produce ended up. The guests, both men and women, reclined on couches and were served a large number of small dishes, eating mostly with their fingers. At such a convivium, or formal banquet, there might be singing and dancing, or poetry reading, or learned conversations. An inscription above the woman on the left says, “Get yourself comfortable, I’m going to sing.”

Unlike the durable mosaics, the dinner-party fresco shows the wear and tear of time. The plaster is cracked and chipped, and the pigment has noticeably faded. Yet it, and other paintings in the exhibition, still effectively describe the social fabric of ancient Pompeii. Other works, such as a spectacular bronze and silver sculpture, Head From the Statue of the Young Bacchus, are simply gorgeous to look at.

Among the first things a visitor encounters in the show are three large frescoes of a garden scene that were displayed in the dining room of a Pompeii villa. One of them, Left Fresco Panel From the Salon of the House of the Golden Bracelet, is fully 12 feet wide and 7 feet tall. It depicts a lush garden — almost a jungle — outfitted with a birdbath, sculptures, and small paintings. With birds flying in the blue sky above, and ferns and flowers sprouting between the trees, it’s a perfect bucolic background for a night of eating and drinking.

Of course, the exhibition isn’t just about life in Pompeii before the eruption of Vesuvius. When the volcano buried the city and its inhabitants, it left behind voids in the solidified lava that later served as molds for castings of plants, animals, and humans trapped in the disaster. The show includes, for example, a plaster cast of a full-size piglet.

The superheated lava from the volcano also produced carbonized copies of everyday products. The show features a wide range of such artifacts, including carbonized walnuts, olives, beans, and wheat, as well as a round loaf of bread, pitch-black and segmented into eight parts.

Near the end, the exhibition displays an epoxy resin cast of the gruesome remains of a young woman found near Pompeii, face down, arms and legs spread, mouth open as if crying in excruciating pain as she died. The “Resin Lady,” as she is now called, had been carrying a bronze jug, a small basket containing several rings and other jewelry, a bag of silver and bronze coins, an iron key, and other essentials for her escape. It’s a shocking, heartbreaking sight.

Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave runs through August 29 at the Legion of Honor Museum, Lincoln Park, San Francisco. The exhibition was organized by the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University, where it was on view in 2019-20 in a somewhat different version. An extensive catalog is published by the Ashmolean.

Top image: Mosaic Panel of a Skeleton Holding Two Wine Jugs (detail), 1-50 A.D., tesserae, National Archeological Museum of Naples, photograph by Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons, image courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.