Little Told L.Á. Perspective

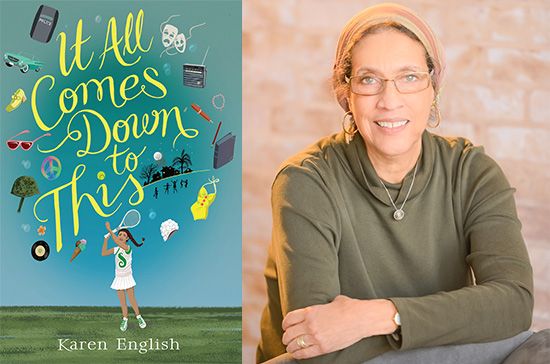

It All Comes Down to This, a middle-grade novel by Karen English, begins with class privilege. “I saw [Mrs. Baylor hauling] herself heavily up the hill,” says 12-year-old Sophie, the narrator, looking out her den window. Sophie’s mother is interviewing housekeepers and this Black woman, Sophie can see, “resented that the hill was steep.” Sophie’s family has recently moved into this two-story house adjacent to the Baldwin Hills. It’s 1965. Los Ángeles. The city and country are beginning to change.

At the outset, the reader learns that Sophie and her family are Black when Sophie describes her mother as having “a Dorothy Dandrige kind of beauty.” Then Sophie introduces brief backstory, saying her family used to live “on Sixth Avenue near Adams,” a neighborhood that’s historically Black. Now, they are the first Black family integrating the upper middle class white neighborhood of View Park, a neighborhood that would evolve into one for wealthy Blacks.

Sophie’s family is already economically privileged because her father’s a lawyer and her mother’s an art gallery curator. These are two high-powered, intellectually demanding, time-consuming, white-collar jobs, making them a rare Black family to have acquired wealth. Sophie’s mother therefore quickly hires the disapproving housekeeper Mrs. Baylor, English briefly mentioning she’s a Jamaican immigrant. English divulges such character-building facts by keeping them appropriately concise, like when Sophie notices Mrs. Baylor’s “…odd scar on her wrist.” English is not interrupting the flow of the narrative to explain the information, which prevents her from talking down to her young readers.

However, from the beginning, Sophie comparing her mother to Dorothy Dandridge indicates why it was easier for her family to acquire wealth and privilege than for the vast majority of Blacks: her mother’s shared light skin. She could pass. Sophie’s at the age where she begins to learn and understand this skin privilege: colorism.

Sophie’s directly confronted with colorism when Mrs. Baylor reveals how she was scarred by colorism as a child—a rare instance of vulnerability—as an apology to Sophie for the cruel remark she made about how Africans would treat light-skinned girls like her. Mrs. Baylor recalls, “[m]y mother did not want me,” because her father “was a very dark man. He looked like an African.” Mrs. Baylor “took after her father.” Through Mrs. Baylor, English powerfully illustrates another way a person can be affected by colorism, complicating the concept by showing how it can be naturally intertwined in our lives, shape who we are and how that shaping reveals a more complex person. English doesn’t hold back on the complex realities of her themes, which creates the novel’s most powerful moments.

Karen English sets It All Comes Down to This in mid-60s Los Ángeles. It’s a diverse city, but with a Spanish fantasy, mythologized, white past, that erases the city’s communities of color from its history. It paints L.Á. as an easeful, unhurried, hospitable place of immense bounty. By English choosing to set her narrative from the point of view of a Black female tween, she’s able to portray Los Ángeles as more authentically complex, through how race and privilege play out in shaping young Sophie. A person both doubly vulnerable and historically ignored, being both Black and female.

Drawn partly from English’s own youth growing up in L.Á., she’s able to vividly bring this changing mid-60s L.Á. back to life as a supporting character through historically specific details that reinforce privilege, colorism and race as driving forces of the novel.

One historic detail is the famous Helms Bakery truck selling sweets and pastries to children across the Westside/View Park, like an ice cream truck, capturing the quintessential suburban feel of the neighborhood. Helms is the bakery that supplied bread to the Olympic athletes during the 1932 summer games. And in mid-60s L.Á., at 12, Sophie is just naively innocent enough that she can still partly see the “magic” in the world through wonderous eyes, excited to see the truck. “My mouth watered as the Helms driver stopped next to me…he dashed around…to reveal the ‘magic’ drawers,” illustrating the typical Americana Sophie now lives amongst.

Yet, as Sophie’s L.Á. begins to grow, she’s confronted with her tenuous place within it. As English based Sophie on her younger sister, she’s able to find these believable tenuous situations and bring out their nuances.

One nuanced situation occurs when Lily, Sophie’s older sister, tells Nathan, Mrs. Baylor’s son, she wants to go with him and Sophie to white Zuma Beach in Malibu. Sophie listens to the exchange from the back seat of Nathan’s car before they leave. “You are definitely a west side girl,” Nathan responds. “You ever been to Watts or Compton, or east of Arlington?” East of Arlington is an early version of the racist shorthand “South of the 10” Angeleños use to refer to Black, South Central Los Ángeles and its supposed dangers. This loaded L.Á. colloquialism reveals how dark-skinned Blacks are resentful of the real or perceived notions of privilege and “selling out,” light skinned Blacks are afforded and engage in, to get ahead, leaving their Black community and culture behind. This perspective is how Lily subconsciously sees herself and her world, as whiter, as the life their parents made for them, shifts their world towards the white Westside.

However, the sisters’ privilege only affords them so much freedom within Los Ángeles, when Nathan gets pulled over by the LAPD in the lily-white Palisades neighborhood. They’re heading home from this memorable day at Zuma, and the cops assume Nathan is associating with white girls. English appropriately lays bare this chilling, perilous reality—policing of Black bodies—young people need to confront like Sophie. “Just what are you doing with that nigger?” a cop asks Lily, way more reminiscent of the South. Sophie’s eyes get “as big as saucers,” shocked at the cops bluntness and the fact it’s happening in her presence. The easeful, hospitable Los Ángeles of the Spanish fantasy, nowhere to be found.

*

The novel’s racial tension culminates in the Watts Rebellion, sparked when Marquette Frye is arrested for drunk driving—though “the boy had no problem walking a straight line.” It peaks when Sophie’s mother demonstrates the systemic racism she’s internalized. Lily calls out her mother’s privilege as “elitist,” after her mother says, “something about a bunch of fools burning down their own neighborhood” during the uprising. Lily demonstrates an awareness of her family’s skin privilege her parents don’t have, arrived at from Nathan’s ideas gained as a college student and from her experience looking for a missing Nathan in Watts after the Rebellion begins. Especially after her mother says, “[if] people work hard,” insinuating her disdain for Watts’ darker hued residents.

Here, English naturally captures Lily’s personal and political growth, and to a lesser extent Sophie’s: the generational shift in understanding how privilege, race and colorism work, to a more nuanced understanding focusing on systemic factors for how they function and why the Rebellion occurred. It’s through Sophie’s thought process that English pulls this off, allowing her young readers to work through this new complex reality along with Sophie.

It All Comes Down to This brings Sophie’s little-told 1960s Black L.Á. perspective to vivid life. The reader is immersed, experiencing Los Ángeles from her 12-year-old place within it. A time period in L.Á. not often told through the eyes of a child of color. Sophie’s experiences show how privilege does not always protect people from colorism and racism, in a way authentic to her character and her age. English never sacrifices the complexities of her themes and story at the expense of her young audience.

(Featured image of View Park, CA by Jules Kain and released as public domain for Wikipedia)