In her poem, “The Trees of the Talmud,” Jacqueline Jules writes,

The Talmud and the Torah

don’t offer logical numbers.

Only advice to plant first

and welcome the Messiah later.

To put every sapling in the ground

Without counting how many years

Before you or your children taste fruit. (51)

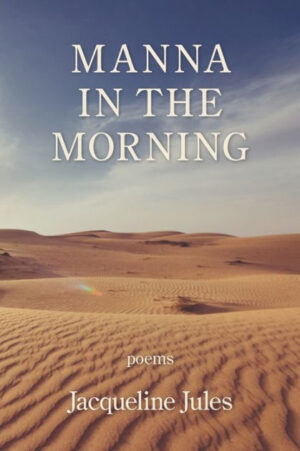

In her newest collection of poetry, Manna in the Morning, Jules’s poems reach through the pages to offer metaphors and considerations for living that distill down what feels complicated into something necessary and lucid – just plant the trees – everything else will follow. Especially today, when we have been through so much, the book is a comfort. It reassures us, through the contemplation of Biblical stories and verses, that we are certainly part of this world and that not only do we undoubtedly belong in it, but we are also vital to it. Our feelings of despair or anguish do not separate us from our communities, but instead make us a part of our communities.

In Mary Oliver’s beloved poem, “Wild Geese,” “the world offers itself to your imagination, / calls to you like the wild geese, hard and exciting / over and over announcing your place / in the family of things.” I like to believe we do all have our place “in the family of things.” We belong. We are part of the world and its magical, mysterious workings; but if you are anything like me, there is a loneliness, a separateness, that is often present. Being human is a difficult undertaking, and this is what makes books like Jacqueline Jules’s so extraordinary. She reminds us, poem by poem, that we are part of something larger than ourselves.

Although we might rejoice in our best moments and wallow in our worst, Jules’s “Biblical Lives” offers that we are not defined so simply by the good and bad we contain or create: “consider the whole saga,” she writes, “And each one of us / is Abraham and Sarah, / Isaac and Rebecca— / more complex / than our worst moments / or our best” (13).

The mythological history we have in the Bible, the narration that Jules provides in the poems, and our own reading of those moments and how they might show up in our own lives, creates a collage effect in the book, each word, image, allusion—the material of poetry—layered upon our own experiences. Take the poem “Lot’s Wife” for example, where the narrator is faced with two roads, a sort of crossroads, and must decide which to travel:

Closing my eyes, I hit the gas,

thinking of Lot’s wife,

and how she turned into

a pillar of salt

when she looked back. (19)

The narrator of the poem uses Lot’s wife as a model of what not to do. Although we are fortunate to have many models in Biblical texts, and in literature in general, it is easy to forget they are there. Often, instead of appreciating our “place in the family of things,” we think of ourselves as going through this journey alone.

In The Early History of Rome, Livy, one of the most fascinating historians of all time, writes, “The study of history is the best medicine for a sick mind; for in history you have a record of the infinite variety of human experience plainly set out for all to see; and in that record you can find for yourself and your country both examples and warnings; fine things to take as models, base things, rotten through and through, to avoid.” Jules’s poems show a narrator who is grappling with those models, and in doing so, reminding us as readers that we also have this tradition of advice to turn to.

In “Jonah and Noah” Jules begins, “In the last hours of Yom Kippur, / as I sit with a rumbling stomach, / reflecting on regrets,” reminding us that our hungers are both physical and spiritual. The stories of Jonah and Noah are meant for our contemplation, but they are also meant for our consumption. They are words to think on, but also words that can sustain us through difficulties. She asks,

Who will I be

As this stormy year unfolds?

The one who sits in the belly of a whale,

Clutching anger, frustration, and fear?

Or the one who finds wood and builds a ship

To survive the oncoming flood? (21)

Jules leaves the poem with that question, and I find myself cheering for the building of the ship. However, Jules’s work also gives the reader a sense that as humans, we are always doing both—perhaps holding onto the fear while concurrently building the ship. Each poem shows us what, as Livy suggests, we should model ourselves after and what we should avoid, but in doing so, also makes us feel that part of taking our place in the universe means accepting our faults as we strive to do better (remember that line about being more complex than our best and worst moments?).

While Jacqueline Jules’s Manna in the Morning reminds us that we can look to the past for guidance, it is also proof that divineness manifests itself in the present us. In “Mirrored Light” Jules ponders the moon’s light, and “how luminous / my life would be, / if I could mirror light / from the heavens / like that” (23) and yet, that is exactly what these poems do. Each one is a mirror in which we see the attention of the poet, a divine gift. In “Crossing the Red Sea,” Jules points out the problem of inattention. When Reuven and Shimon crossed the Red Sea, “they missed the miracle / of the waters parting” (33). It is the poet who focuses our attention back to the waters, back to the miracle. Attention gives us the miracle; it gives us exactly what we need:

Like the favorite dish

a parent cooks all afternoon

to please a child,

manna was a special treat

on each tongue. To some,

it tasted like bread. For others,

it was honey. Gathered by hand

from the desert, it became

whatever was desired

in the exact portion needed. (“Miracles in the Desert” 38)

Manna in the Morning is a collection to cherish and to gift. Jules’s poems are readable and profound. As Jules ponders Leviticus 20:26 in “You Shall Be Holy,” she writes, “‘Shall’ to be understood / as a command, not suggestion” (52). These poems are Shalls. They proclaim our connection to what has come before, rooting us in tradition, while simultaneously gathering up possibility and meaning for us to exult in, commanding us to flourish outward. They are the saplings that are planted for a future harvest, but they are also the harvest.

Purchase Manna In the Morning

Photo credit: Alexis Rhone Fancher