Dublin has James Joyce, Wessex has Thomas Hardy, mid-town Manhattan has Don DeLillo, and now Venice, California, that erstwhile ocean-side slum, has poet Tom Laichas, author of the new book Three Hundred Streets of Venice California. Once for a brief while I sat across a coffee table from Tom (this was one of those coffee table poetry workshops) and was immediately impressed by his ability to plunder history and the sciences for arcane and apt details. That uncanny feel for the odd and significant pervades this new book. In poems that range from short, imagistic pieces to longer meditations on family, place and time, he limns an unsettling portrait of one of the American Dream’s westernmost outposts, surfurbia, from the mid-20th century to the present.

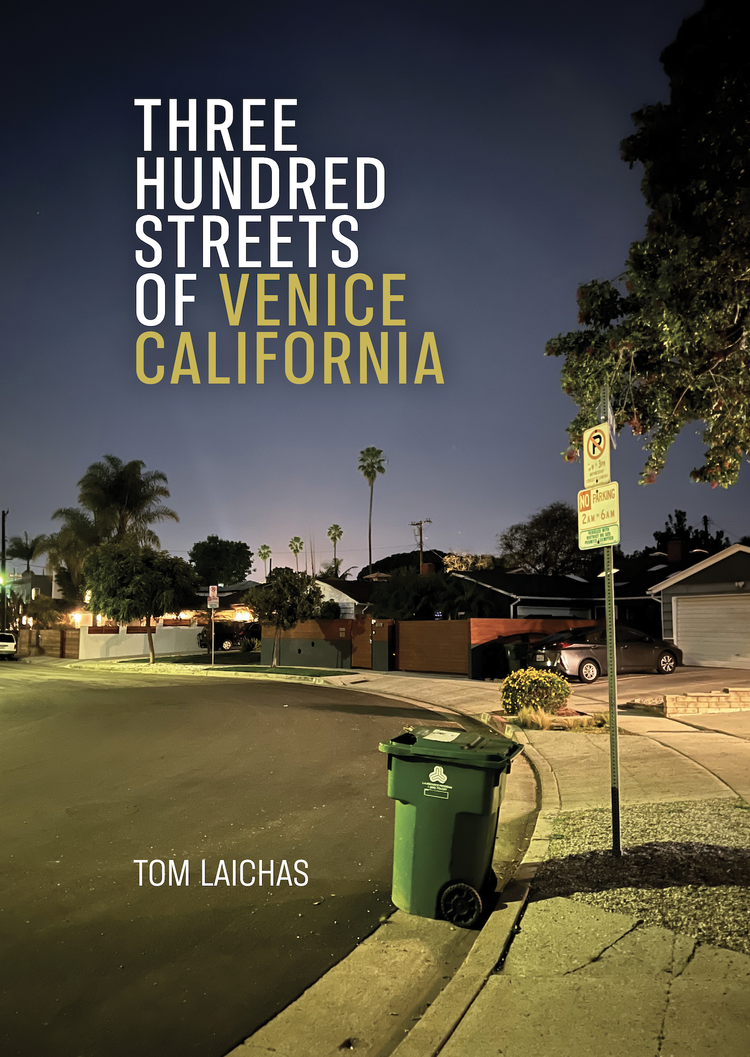

Look at the cover image, a Laichas photograph depicting an austerely empty suburban street, devoid of human presence, and one is struck by its casual surrealism, its striking resemblance, say, to Magritte’s L’Empire des Lumieres.

Neither a community, nor even a group of neighbors, Venice is home to the Lonely Crowd, those economic atoms that fuel neo-liberal capitalism. (Almost) none of the neighbors have names, and they’re not happy about it. They want their individualism, and they want it now. In “Ozone Av” one of the “neighbors” calls him out: “Why write about streets? Why not write about people? It’s like your streets are empty?” And then she adds, stingingly, “My name isn’t neighbor.”

The poet acknowledges the truth of her accusation; but for him it’s a feature, not a bug. He’s a solipsist, shy, easily overwhelmed by noise and people. Given the choice he would rather be a ghost than a neighbor among neighbors. Ghosts, he tells us in “Woodlawn Av,” are like writers, “ruins-in-reverse, falling away from death’s entropy towards articulate spiritus. Some ghosts prophesy, predicting the irrational past.” In a different time and place, he might have been hanging out with Yeats in that tower in Ballylee, “studying monuments of [the soul’s] magnificence” and learning to sing of “what is past, or passing, or to come.”

But no, he is just a curious, well-read American suburbanite, forced to commingle with others of his exasperating kind. How dreary! How soul deadening! “Another American Venice,” for instance, offers a deadpan disquisition on the deadly boredom of American cities; Venice, FL, he tells us, is “so much like my beach town: three homeless shelters, a McDonald’s, a Chick-Fil-A. Here are births and deaths, weekending vacationers, invasive species, warming tides, police helicopters, concerned neighbors.” I think we know what Yeats would have made of this: “That is no country for old men. The young / In one another’s arms, birds in the trees, /—Those dying generations—at their song,” Where Yeats is tragic, Laichas is satiric, almost dyspeptic.

The dream that created such a place arrived on this continent with the first Europeans: the poem “Boone Av,” a street named for that ever-westering explorer, is a fantasia of manifest destiny, but more pointedly a critique of the restlessness that underpinned westward expansion, civilization (that noble enterprise) coming to destroy the wilderness. Reading Laichas’s acid-etched portrayal of the American Dream, its contradictions and destructiveness, I was reminded of Merwin’s “The Last One” and Kinnell’s “The Bear,” to name just two (Tongo Eisen-Martin’s Blood on the Fog also came to mind):

The dozers flayed Boone Avenue’s body, tanned the stretched skin, and divided the hide into house lots.

Out of respect, they kept the name.

Westering out cross-continentally, Boone was an American street. Some die so that others might live free in two thousand square feet, four en suite, and Corian counters.

Pioneers! O Pioneers!

Interesting, that final nod to Willa Cather, whose relative sunniness seems a fitting contrast in this conext.

As small as the community is, it is riven by class. As the poet observes in the poem “Thatcher Yard,” the quality wants a higher quality of life; they want to truck the junkies, the muggers, the homeless, and the poor to Barstow and Victorville, out in the desert.

My neighbors want a beachside Henry James:

cleaned-up streets for people who will pay the bed and breakfast rent,

walk the Sunday boardwalk, burn their beach skins on the lemon sand

But to what end? This gentrifying gentry are almost as transitory as the tourists. What George Oppen observed about New York City is also true of its shabby-genteel after-image. The people come and go, even as the place remains. Laichas asks us to consider, for example, a house on “Rennie Av,” in which we encounter not just the history of a house but the evanescence, the fictiveness of “ownership”:

In ninety years the house on Rennie has had ten owners.

These ten called themselves I and called this house mine. . . .

After the tenth, others will come, Perhaps a couple: one, a school teacher; the other, a quality control engineer. . . .

One day, this couple’s children, now adults, will take their parents aside. You’ve been falling a lot. Don’t you think it’s time to sell.

It may be too much to ask but in “Berkeley Dr,” Laichas asks for a different kind of neighbor, one like the childhood friend whom Czeslaw Miłosz celebrated: He sought strong flavors. He fled from kitsch. Is he addressing the reader or himself when he asks:

Don’t you seek strong flavors? Don’t you shrink from sentiment? Aren’t you convinced of the past and its power? Don’t you sometimes wonder whether neighbors fly toward history’s klieg-lit heat like moths towards nightmare?

We’re left with a question then, aren’t we? Are we just neighbors, or do we risk becoming a friend? This book is haunted by time and loss, and it is the writer who does the haunting. He has no fixed sense of time or self, but only a permeable sense of who he is. As he tells us in “Washington Bl (V)” he is himself and his “otherselves”: “The otherselves tell me they’ve seen this before I was born. I remember their remembering. I’m their ghost.” The ghostly historian has seen it all, still sees it in fact, the bounty of youth, the less bountiful present. “Miles into summer, so much lives on” (“Gardenias”). He is, in fact, a figure like Tiresias in The Waste Land, who has been to the Unreal City and knows that April is the cruelest month.

*