Salvage the Story: Review of We Are All Armenian: Voices From the Diaspora

When the novelist Chris McCormick traveled to Armenia to conduct research for a novel set in his mother’s hometown, he did so at an unusual point in the writing process: he had already finished the novel. McCormick’s research was not intended to enrich a work-in-progress. Rather, McCormick interrogated the completed work and his imaginative process. He traveled “to see a place [he’d] imagined all [his] life” and compare his imaginative construction to the real thing.

McCormick visited the Temple of Garni, a first century pagan temple restored through anastylosis, a reconstruction method that combines original pieces with new materials: “Where the Garni restorers had to use new materials, they chose blank stones that stood out next to the ancient ones, the difference between the materials stark. They wanted visitors to be able to discern between the original and the added. In this way, I could see exactly what had been salvaged and what had been supplied.” The reconstruction does not create the illusion that the ancient temple is in its original state. What’s lost, what’s salvaged, what remains—all are honestly presented. McCormick finds in this hybrid reconstruction an analogue to his fiction: “[As] I compared the spongy touch of the ancient basalt to the smooth faces of the blank stones, I considered the combinations of memory and imagination I was really there to investigate. A kind of inventive anastylosis, memory and imagination, only I wasn’t sure which was the original and which the support.” For McCormick, anastylosis, mixing old with new to create something that stands anew, captures his creative process as a diasporan Armenian author at work with the materials of the imagination, of memory and family history.

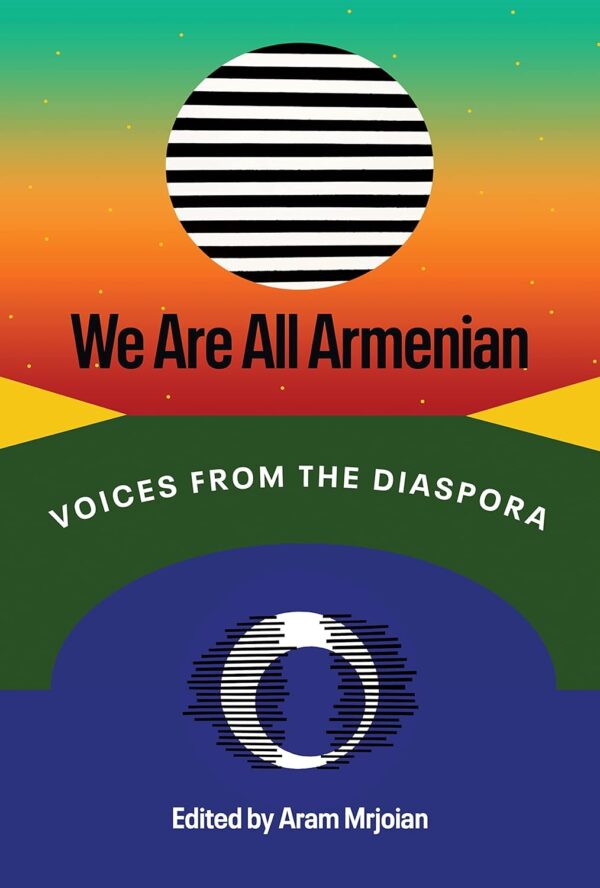

McCormick’s “My Armenia: On Imagining and Seeing” is one of eighteen urgent personal essays collected in We Are All Armenian: Voices From the Diaspora, a new anthology edited by Aram Mrjoian. Mrjoian, an editor for Guernica, has curated a cohesive volume of contemporary diasporan Armenian writing, attentive to those marginalized within this global minority. Mrjoian opens his introduction on April 24, 2021, when President Joe Biden formally acknowledged the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1923 in which Ottoman Empire leadership orchestrated the murder of an estimated 1.5 million Armenians in Ottoman lands. Many Armenians escaped the atrocity, which, now a century old, marks the genesis of the Armenian diaspora. The Genocide explains how, as Mrjoian notes, Armenia has a population of three million while the global Armenian population numbers around eleven. In We Are All Armenian, we hear from the grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and great-great grandchildren of Genocide survivors. For diasporan authors separated from an ancestral homeland, Armenian identity is both central to their lives and, at its core, incomplete, fractured, dislocated. With some pieces stolen and others eroded by time, these identities enact, by necessity, an anastylosis of self to endure.

For the Armenian diaspora, their ancestral home is not the nation of Armenia, but a region known as Western Armenia in the east of Turkey, the nation that superceded the Ottoman state. Home to few Armenians today, Western Armenia is at once distant geographically and off the map. This explains why, when an American bigot yells at nine year old Sophia Armen, in the days after September 11, to “go back to your country!” she admits, “I can’t” and “It does not exist. Not really.” In “Where Are You From? No, Where Are You Really From?” Armen, like McCormick, turns to a metaphor of brokenness to contour diasporan identity and map new geographies of home: “Because the Armenian diaspora from the genocide lives across the world like shattered glass, it’s a community you cannot reassemble into what it was. So we have to make it into something else, something more beautiful—a mosaic of sorts, with its pieces.” Armen’s mosaic, like McCormick’s “inventive anastylosis,” presents an identity, a community, an imagination in the process of being made whole. If to be a diasporan is to be a reconstruction, diasporans have a multitude of ways to construct themselves as Armenians. For Armen, the development of Armenian identity is mixed with commitments of organizing and activism. The diasporan perspective allows Armen a wide lens on oppression, an ability to see connections between, for instance, the dispossession of indigenous tribes of North America and the uprooted Armenians of Anatolia.

For the contributors to We Are All Armenian, the act of writing creates more than pieces of writing: it affirms contested histories and proclaims the survival of a people. Kohar Avakian brings together different strands of a remarkable family history which includes survivors of three atrocities: Western Armenians, African Americans, and Nipmuc. In a remarkable passage, she notes the common omission that characterizes the histories of her disparate peoples of indigenous, old, and new worlds. In school she never learned the history of the Nipmuc despite living on Nipmuc land, or the full history of African Americans, “the nation’s true founding fathers and mothers.” And for the past century the Turkish government has denied the Armenian Genocide even took place. Avakian has found a vocation in these omissions, in writing occluded histories: “My ancestors had survived and thrived despite all attempts at their decimation so that I could be here today. They deserved to live and have their stories of survival celebrated and told, just like my Armenian predecessors. For them, I write.”

The late Naira Kuzmich finds in the wounds of Armenian history a necessary disruptive quality—one that prevents her from seeking historical closure and cheap reconciliation. She recounts an incongruous moment at a bar in Berlin dancing with young Germans to the Jewish folk song “Hava Nagila” when a Turkish man joins her circle. The layered absurdity and symbolism are not lost on Kuzmich, who refuses to find redemptive poetry in this dance of descendents. In fact, Kuzmich finds in the yearning for reconciliation, for closure, for trading the past for a hopeful future, a particularly white American attitude toward history—after all, Kuzmich writes, “[white Americans] have been trying to dismiss history for centuries.” Reflecting further on her inability and unwillingness to find reconciliation in the dance, she writes, “It was the past there intruding on the present—but I welcomed that intrusion. I welcome it still. I needed it to understand that history is not the passing of time but time’s inability to heal all wounds.”

Friction between layers of history is the subtext of Hrag Vartanian’s “The Story of my Body,” a fraught meditation on the body as a site of legal contestation, of physical and bureaucratic abuse. Throughout his life, Vartanian, an Armenian, a Canadian born in Syria, a gay man, finds his body, his “topograph[y] of nowhere and everywhere,” targeted—first by sexual predators, then by bigots, then by more structural forces. Living in New York City following 9/11, Vartanian is forced to join the War on Terrorism’s first “Muslim registry” that tracks and surveils him, limits his movements and confronts him at every border. While 9/11 provides an immediate cause of these indignities, Vartanian’s precarious status ultimately traces back to a diasporan’s original dislocation. “Being Armenian has felt like a heavy burden, and more so at borders,” he writes, “where the lines that transverse the world, dividing us into imaginary teams, also disrupt our families, severing parts for decades—or forever—into fantastic and complicated schemes that rip apart and reconstruct our more intimate lives into something unrecognizable. Those borders transverse our bodies as well.” One cannot consider the borders that delineate lands apart from the lives of physical bodies and their legal delineations. To be at home, Vartanian implies, is to be at home in a body, and vice versa.

Kohar Avakian’s themes of omission and vocation find echo in the volume’s closing piece, photojournalist Scout Tufankjian’s “We Are All Armenian.” Tufankjian traces her calling to photojournalism to an encounter with a middle-school history teacher who denied the existence of the Armenian Genocide, and recounts her recent project to photograph diasporan Armenians across the globe. Her photography makes visible the existence of a people and culture. Her photographs are imperative acts: “I channeled my child’s fury at my denialist history teacher into a career where I demanded that others see the things that I have seen.” Photography helps Tufankjian locate herself in a culture in which she has felt, at times, a fraudulent belonging. The essay culminates in a deeply personal realization that nevertheless speaks for those assembled in the anthology:

I had grown up thinking that there was a tiny box you need to squeeze into to be a good Armenian, a box that I did not fit in, but my travels showed me that there is a place for all of us within this huge Armenian family, whether we are half Armenians, gay Armenians, Black Armenians, arty Armenians, atheist Armenians, non-Armenian-speaking-Armenians, or good old-fashioned 100 percent Armenian AYF/AGBU-belonging/churchgoing/future-engineer Armenians. We are all Armenian. All of us have a role to play in the future of our community. Even me. What I had thought was my lack of belonging was in fact my way of belonging. While my sense of this belonging may have been fractured, I did, despite it all, still belong.

We Are All Armenian is an anthology precisely tuned to our time of dislocation and international migration, and to debates surrounding historical injustices. The anthology’s focus on stories of the Armenian diaspora, a global population of eleven million entering its second century, does not limit the book’s relevance but widens it: the contributors’ intersecting commitments and incisive articulations of diasporan subjectivity will make this book resonate with a broad audience in a world of many diasporas and dispossessed peoples who wish to salvage their many stories.

*