The high school football massacre on ESPN over the weekend, number two ranked IMG Academy beating Bishop Sycamore 56-0, is a reminder that not everyone is cut out for athletics. I count myself in that number, as I spoke about on a Razorcake podcast with fellow guests Myriam Gurba and John Ross Bowie, I undertook a brief and ill-fated exploration of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. I had a lot more fun for a few years in a community surrounding a Los Angeles CrossFit gym called Merge, which changed names and owners a while back. We had friendly individual and team competitions which brought out the best in everyone and led to a lot of inspiring moments. Sometimes I contemplate returning to some sort of physical activity, maybe a Muay Thai school or a judo class, but I was never one for a pickup game of basketball or football in the park. I seriously doubt my athletic abilities and feel like a fraud when I look at the treadmill and weightlifting equipment collecting dust in my garage.

As it turns out, I have a lot more claim to legitimacy than some National Hockey League draft picks and New York Mets featured in Sports Illustrated profiles. I shouldn’t be worried about impostor syndrome when it comes to sports, because sports already has a large assembly of impostors in its history.

On August 1, 1898, British newspaper The Sportsman published an upcoming horse racing card as called in by the clerk of Trodmore Hunt Club in the county of Cornwall. Bets were placed, results were reported as wired in by a freelance reporter named Martin hired specifically for the event, and bookies paid out on wins. Another paper, The Sporting Life, had not sent anyone to the event and simply copied the results from Martin’s report at The Sportsman, but they accidentally printed winning horse Reaper’s 5-to-1 odds win as 5-to-2. The discrepancy prompted an investigation to verify the actual odds, and then police involvement once Martin disappeared. The first discovery that indicated something was afoot—no village called Trodmore existed in Cornwall. It had been a scheme to collect longshot gambling wins for payouts totalling the 19th century equivalent of about 13 million pounds (about 18 million USD).

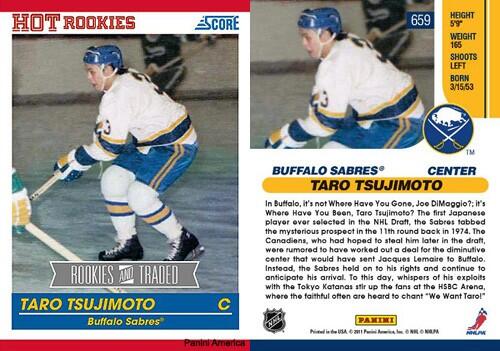

Nearly a century later, sports went from horses that didn’t exist to actual human players—that weren’t actually real. At the end of May 1974, the 12th annual NHL Entry Draft took place over three days on a supposedly secret conference call so that rival World Hockey Association wouldn’t poach picks. This process slowed things down considerably and didn’t stop leaks, to the frustration of many of the teams and their leadership, including Buffalo Sabres’ General Manager George “Punch” Imlach. By the time round 11 rolled around and Punch was up for pick number 183, selected Taro Tsjuimoto of Japanese Ice Hockey League’s Tokyo Katanas. The problem was, while the JIHL was an authentic entity from 1966 until 2004, they had no Tokyo team at the time. A katana is a sword, just like a sabre, but there was no Tsujimoto coming to Buffalo. He was a fictional character made up by Punch in protest of the draft procedures. It wasn’t until after the draft pick had been accepted and published in sports news reports, the name listed on the Sabres’ training camp roster and a stall set aside for Tsujimoto, that Punch fessed up. The league would go on to list round 11, pick 183 of the 1974 draft as “invalid claim.”

The Boston Bruins, on the other hand, had a real life writer who briefly trained with them as a goalie in 1977. Co-founder and first editor-in-chief of the Paris Review, George Plimpton, was also an amateur athlete who got to try out amazing sports experiences to write about later. It began as far back as 1958, when he pitched against National League baseball players before an exhibition game. In 1959, he barely lasted three rounds in a sparring bout with Light Heavyweight boxing legend Archie Moore. In 1963, he trained as an NFL quarterback with the Detroit Lions. A few years later, he played on the PGA Tour for a month alongside Jack Nickalus and Arnold Palmer.

But his entry in the annals of sports hoax history was earned with an Apri 1, 1985 feature in Sports Illustrated when he penned the tale of Hayden Siddhartha Finch, a New York Mets pitcher that didn’t exist. The magazine’s managing editor, Mark Mulvoy, commissioned the piece along with a photo shoot using a stand-in named Joe Berton. Sidd’s life story, which was released in late March and caught nationwide attention, was of a French horn player and Tibetan yoga student who could throw a 168 mph fastball, but preferred to take up golf instead of continuing a career in the Major League. Berton was brought in for an April 2nd press conference where, as Sidd Finch, he announced his retirement from baseball.

While Plimpton’s efforts were sanctioned, the impersonations of “The Great Impostor” Barry Bremen of Detroit, Michigan garnered him arrests and fines. The NBA All-Star Game in February 1979 took place in the Pontiac Silverdome, where Bremen snuck onto the court in a Kansas City Kings uniform and began warming up. King guard Otis Birdsong didn’t recognize him and Bremen was removed. In June of that year, Bremen got away with a practice round at the U.S. Open golf championship. A month later, posing as a New York Yankee, he caught fly balls in the outfield before the Major League All-Star Game. He would repeat these stunts for years in various uniforms and increasingly more sophisticated disguises, including losing weight and practicing routines for months before a quickly aborted mission as a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader.

England had its own sports prankster in the early aughts, a Brit Pop scenester named Karl Power who was first immortalized in Black Grape’s 1996 song “Fat Neck,” then performed his own form of art first in 2001 by crashing the field to take the team photo with Manchester United before their game against Bayern Munich. Later that year, he had bat in hand and walked onto the cricket field at Headingley Stadium when England was to take on Australia. During 2002’s Wimbledon, he played a short game of tennis with an accomplice on the Centre Court. That same year at the British Grand Prix motor race, he made it onto the winners’ podium. It was another 2003 attempt during a Manchester United game that got the team to ban him for life.

The team from Bishop Sycamore this past weekend were permitted to be on the field, of course, though perhaps they should never have been. ESPN was told by the school they had Division I prospects, but the network could not verify the claim before allowing them to participate in the GEICO ESPN High School Football Kickoff showcase. It was reminiscent of another player who fibbed about their resume, Southampton Football Club’s own Ali Dia. In 1996, Dia was contracted as a striker, a role he received after an impostor claiming to be FIFA World Player of the Year George Weah vouched for Dia with Southampton manager Graeme Souness. The fake Weah told Souness that Dia was his cousin and an experienced player, when in reality Dia had only had a mediocre (if not poor) career in lower levels and non-league play. Dia was brought in as a substitute 32 minutes into a game against Leeds, then pulled after 53 minutes of terrible playing, and then released from his contract only after two weeks. (His son Simon Dia has gone onto a much more respectable career as a forward, presumably with no phony phone calls needed.)

As the methods and technology behind surveillance, security, and mitigating identity fraud have continued to evolve, all these kinds of machinations have grown more difficult if not impossible to pull off. We may now be past the point of the rogue sportsman…though when it comes to catfishing and the dating world, linebacker and current free agent Manti Te’o may tell you to still stay frosty.