After a mostly peaceful century in Europe, the Great War of 1914-18 really created the modern age. Along with killing 20 million soldiers and civilians, bankrupting Germany, exhausting the British Empire, collapsing the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, and setting off the Russian Revolution, it changed the way wars are fought and how they’re documented and explained to civilian populations.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art has mounted a sprawling exhibition that seeks to show how World War I news coverage, propaganda, and even fine art were enlisted in the battles for hearts and minds. Imagined Fronts: The Great War and Global Media includes plenty of documentary photographs and films of the fighting, though the bulky cameras of the era limited their effectiveness on the battlefield. The show also features modern artists’ interpretation of the war and its effects, as well as a group of remarkable posters that illustrate how governments tried to sell the war to their civilian populations.

John Armstrong Turnbull’s Dogfight of 1918-19 (above and detail in top image) captures the chaos and speed of fighter planes in battle, using an angular, modern style that looks similar to German Expressionism and Italian Futurism. The little-known Turnbull, described in the exhibition as a Scottish pilot who was associated with the Vorticist group of artists and the Bloomsbury group of writers, clearly understood how the war was fought high up in the sky. The viewer is placed in the pilot’s seat of a British fighter plane as it heads into a snarl of at least five other German or British planes. It’s a knockout picture.

Most of the war was fought on the ground, of course, and mostly from networks of trenches on both sides of the front line. Unlike some action-packed photographs in the exhibition, however, Paul Castelneau’s Autochrome photograph First Line Trench, Hirtzbach Woods, France of 1917, unexpectedly documents a group of French soldiers in the decorous style of a 19th-century group portrait, except for the setting in a trench rather than a men’s club.

Felix Edouard Vallotton’s oil painting Verdun of 1917 is far more successful in depicting the true face of war. The forest in the hilly landscape is on fire, thick black smoke billows up from the valley below, and the sky is streaked with red and black and blue trails of incoming artillery shells. It’s a hellish scene, but one that’s perfectly suited to its modernist style.

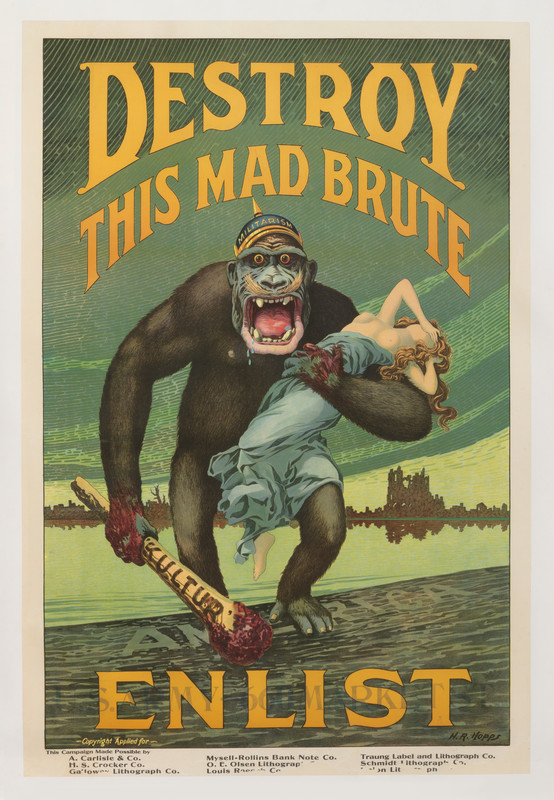

Some of the most interesting works in the show have nothing to do with the battlefield. Instead, they’re propaganda posters, designed not to document the actual war but to change civilian hearts and minds back home. Among several examples of old-fashioned patriotic posters is the iconic image of Uncle Sam in his top hat, pointing to the viewer and saying, “I Want You for U.S. Army.”

The most visually striking posters, though, are the outrageous ones. Among these is one by August William Hutaf for the U.S. Tank Corps that screams “Treat ‘Em Rough! Join the Tanks” and features a gigantic black cat, with teeth and claws bared, flying above a cartoon battlefield dominated by tanks.

A 1918 poster by Harry R. Hopps takes aim at the German enemy, depicting him as a savage gorilla. Below the title “Destroy This Mad Beast” is a gigantic gorilla wearing a German military helmet labeled “Militarism” and carrying in his right hand a huge wooden club labeled “Kultur.” The gorilla is walking onto a beach marked “America,” and in his left arm he holds a half-naked young woman, a classic damsel in distress who covers her eyes in horror. It’s completely over the top, but probably persuaded some patriotic young men to enlist.

Though the Great War officially ended with the Armistice of November 11, 1918, the aftereffects continued for years, especially in the form of the Russian Revolution. The German economy struggled under the harsh terms of the peace treaty, and the exhibition includes an interesting section on this postwar period. With out-of-control inflation and a German currency that became almost worthless, the average German farmer was in a tight spot.

A 1919 poster by Bruno Haunickel explains the situation clearly. A German farmer on the right offers a wad of paper money to a Dutch farmer holding a big red wheel of Edam cheese. The caption above says, in German, “Paper? No!” The Dutch farmer goes on to say he’ll take the German’s coal and potash and machinery, but otherwise he’ll keep his own cakes, bread, and butter, urging the German to “create goods.” It would take a worldwide depression and the Second World War before Germany achieved its potential to do just that.

Imagined Fronts: The Great War and Global Media runs through July 7 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5900 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles. An exhibition catalog is published by LACMA and Delmonico Books/D.A.P.

Featured image: John Armstrong Turnbull, Dogfight, 1918–19, oil on canvas; Canadian War Museum, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.