The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, has mounted a small but impressive exhibition of American art from the 1930s and 1940s. Art for the People: WPA-Era Paintings From the Dijkstra Collection includes 19 works, all of them more or less realist images, many with California subjects.

In the 1930s, when much of Western art was still under the influence of Cubism and Expressionism, Roosevelt’s New Deal launched the Works Progress Administration. The WPA supported job-creating projects such as roads and bridges but also commissioned public works of art that celebrated ordinary workers in an accessible style. The Dijkstra collection includes a handful of these typical WPA paintings, though it also features elegant landscapes and cityscapes as well as quiet portraits and still-lifes that have little to do with the working class.

Hugo Gellert’s Worker and Machine of 1928 (above and top image) depicts a muscular young man in a red shirt who holds a large wrench in his right hand as he prepares to work on the heavy machinery behind him. He’s painted in a stripped-down, almost expressionist style that betrays no emotions, just an intense focus on his work.

Gellert, who emigrated in his teens to New York from Budapest, Hungary, was a committed leftist and member of the Communist Party. Along with painting murals, he contributed illustrations to publications ranging from The New Masses to The New Yorker. Even though Worker and Machine was created before the founding of the WPA, it certainly fits the classic style of WPA art: a celebration of the worker, without any individual eccentricities, a lot like the Socialist Realism of the Soviet Union.

Miki Hayakawa’s From My Window of 1935 is a completely different sort of painting. It’s a quiet, closely observed still-life and landscape of a particular place, in this case San Francisco. In the foreground is a small round table topped by a vase of showy pink flowers. On the window sill behind them sits a row of green potted plants, and beyond is a panoramic view of the buildings on Telegraph Hill, topped by the iconic Coit Tower (which contains WPA-era murals). It’s a classic cityscape.

Hayakawa, who emigrated to California from Japan as a child, studied and lived in San Francisco as an adult. When Japanese-Americans were being rounded up and sent to internment camps in 1942, during World War II, she moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and lived there for the rest of her life.

Helen Forbes, who painted murals for the San Francisco Zoo and several post offices in California during the WPA era, is represented by the elegant landscape A Vale in Death Valley of 1939. Below a dark blue sky, the stripped-down image is a medley of almost abstract triangular shapes in a limited range of tans and pinks and browns. It perfectly captures the emptiness and beauty of Death Valley.

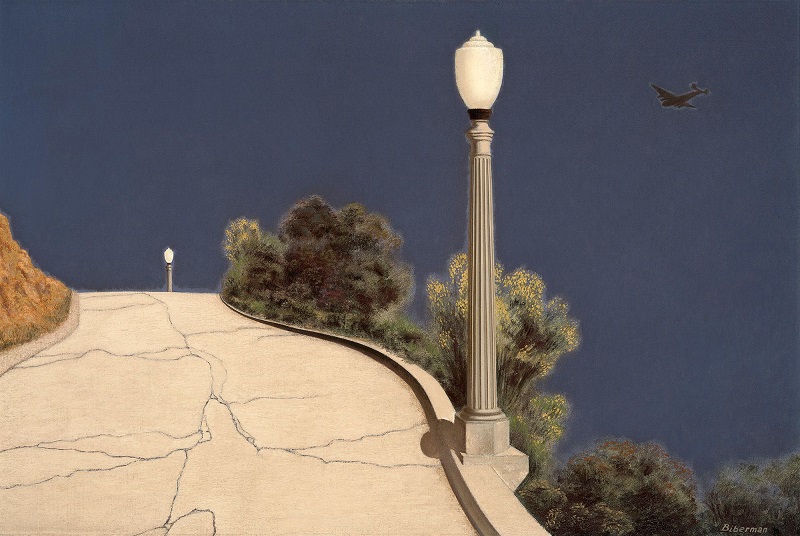

Edward Biberman’s Slow Curve of 1945, which depicts an empty stretch of Mulholland Drive overlooking Los Angeles, is even spookier than Forbes’s Death Valley. With a bit of rocky hillside on the left, and a couple of old-fashioned lampposts and some scrubby trees on the right, the cracked concrete road looks like it will drop off the cliff a short distance ahead. On close inspection, you can see an airplane on the upper right, maybe a B-29 like the one that dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Or maybe it’s just an airliner headed for a landing at LAX.

Biberman grew up in a wealthy family in Philadelphia, lived in Paris and New York (where he came in contact with Diego Rivera), and later landed in Los Angeles. Like Gellert, he was a socialist and a muralist, painting one of the murals installed in the U.S. post office and courthouse building in downtown Los Angeles.

So three cheers for Sandra and Bram Dijkstras, who have donated several artworks to the Huntington, including two in the WPA show. (She’s a successful literary agent; he’s a professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego.) Let’s hope some of the other paintings in the exhibition find their way into the Huntington’s collection in the future.

Art for the People: WPA-Era Paintings From the Dijkstra Collection runs through March 18 at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California. The show was co-organized with the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento and the Oceanside Museum of Art in Oceanside, California, where the exhibition was on view last year.

Top image: Hugo Gellert, Worker and Machine, 1928, oil on board; collection of Sandra and Bram Dijkstra.

The Huntington’s New Goya

If you’re visiting the Huntington for the WPA show, don’t miss the chance to see the museum’s recent acquisition of a spectacular painting by the Spanish master Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828). Portrait of Jose Antonio Caballero, Second Marques de Caballero, Secretary of Grace and Justice of 1807 depicts the Spanish court official of the title in amazing detail. He’ll fit in well with the British aristocrats in the Huntington’s permanent collection.

Caballero wears a gold-trimmed black coat decorated with medals and a big blue-and-white sash across his chest, red trousers, gold-trimmed vest, and an almost friendly, almost haughty expression on his face. It’s one of the artist’s final works as a court painter before Napoleon’s occupation of Spain in late 1807. That changed Goya’s focus to works such as The Third of May 1808, the famous painting in the Prado that depicts a French firing squad executing Spanish resisters.

The Caballero portrait was donated to the Huntington late last year by the Ahmanson Foundation. It’s the third annual gift of a major painting by the foundation, which for decades had given one masterwork a year to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. For art lovers in Southern California, LACMA’s loss is the Huntington’s gain.